A Heartfelt And Troubling Challenge To American Jews

Joshua Leifer’s ‘Tablets Shattered’ – eloquent and insightful but at times frustratingly off base – introduces a voice to be reckoned with.

A full-throated critique of virtually every form of American Jew, especially Zionists, the book was named winner of the Jewish Book Council’s 2025 National Jewish Book Award in the category of Modern Thought and Experience.

Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don't criticize

What you can't understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is rapidly agin'

Please get out of the new one

If you can't lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin'

From “The Times They Are A-Changin’”

Bob Dylan, 1964

Maybe it’s because I’ve been bingeing on Bob Dylan films lately that I’ve been thinking of Joshua Leifer as a kind of budding, 21st century Dylan, the voice of a growing segment of disgruntled Jewish young people rebelling against the ways of their elders – in this case, in what they see as blind support for a “genocidal” state of Israel.

Tempting as it may be to dismiss the 30-year-old author’s stinging rebuke of militant Zionism and what he sees as the steady erosion of American Jewish life, that would be a mistake. Leifer is not an unaffiliated outsider. He was raised in an observant Conservative home in New Jersey, attended a Conservative Jewish day school, studied in Israel during his post-high school gap year, lives in Tel Aviv with his charedi-raised wife, and recently told an interviewer that he’d love to spend a year studying Talumd in an Israeli yeshiva.

What’s more, the publication of his ambitious, much-discussed first book, “Tablets Shattered: The End of an American Jewish Century and the Future of Jewish Life,” which cast him into the national spotlight last summer, is a serious, thoughtful and often spot-on analysis of American Jewish religious and political life of the last 100 years, albeit with some jarring blind spots. With this book, the impassioned left-wing journalist who is pursuing a PhD at Yale University takes on the role of historian, memoirist, activist and sociological prophet – no easy task. He weaves together his personal and family story with historical events and trends in American Jewish life, offering up a complex mix of reproval and compassion. The book presents a full-throated critique of virtually every form of American Jew, especially Zionists, while calling for a communal cheshbon hanefesh, an act of soul-searching, based on the author’s deep engagement with and concern about the future of Judaism and Israel.

The fact that Leifer views Israel as an oppressor state and regrets that many American Jews have allowed Zionism to become their religion should not cast him as an enemy of the Jewish people. To the contrary, though I disagree strongly with his politics, the more I’ve read of his writings, listened to and watched interviews with him – and interviewed him myself – the more I see him as a sincere, anguished ideologue, a kind of modern-day prophet – though a false one, I believe – calling on his people to relent and repent while well aware that he is speaking from a painfully lonely space. In the wake of October 7, he has been cast out by many of his fellow-progressives for publicly rejecting their embrace of Hamas’s murderous cause as well as by Jews who are repelled by his anti-Zionist rhetoric.

“As a Jew and as a progressive, I often feel closed in on from both sides, pinched between great shame and great fear,” he writes in a post-October 7 “Afterword” to Shattered Tablets. “I am infuriated by the crimes of the state that acts in my name” [Israel], “and more worried than I have ever been by the rising acceptability of conspiratorial thinking and the demonization of Jews. It often feels like an impossible place.”

Unlike Bob Dylan, who chose to spar with and often mock the media, keeping his thoughts and motives to himself, Leifer has been remarkably candid, even eager to engage with those who disagree with him. He told me he has been “pleasantly surprised and encouraged, given my political views,” by the reception he has had in appearances in local Jewish communities, including synagogues, during his national book tour. “Different communities have different problems with the book,” he said, noting that the most negative reviews have come from the left, his political base, because of his refusal to renounce Israel with finality.

I have my own differences with the book, which I’ll explain below.

Botched Book Launch

Leifer learned just how toxic his book’s themes are when the planned launch of “Tablets Shattered” at a progressive book store in Brooklyn last August turned into a widely reported fracas that underscored the deep divisions over Zionism, and what it even means. Leifer was scheduled to be interviewed by his friend, Rabbi Andy Bachman, former spiritual leader of a prominent Reform temple in Brooklyn, but the event was canceled at the last minute “due to unforeseen circumstances,” according to a sign on the bookstore door. In fact, it soon became clear, an employee of the store decided to cancel the event – not because of Leifer’s politics but because she learned that Bachman is a Zionist.

The botched launch made headlines, increased interest in and sales of the book, and set off a new round of discussions about the lack of serious debate in the community. The New York Times Sunday Book Review (September 29) devoted the full cover to “Tablets Shattered,” quite an achievement for a first-time author. The review, by Sam Kriss, presumably a secular Jew, was mixed, chiding Leifer for concluding “that the only way to preserve Judaism is to return to observance, the byzantine rituals that keep Jews apart.” Kriss described the book as “a jeremiad,” lamenting the failure of the children of Israel to follow God’s laws.

Leifer does take Jewish ritual and law seriously. He explains at the outset that the book is “the result of my past and present grappling with Judaism, America and Israel.” He considers it an “urgent task” and confides that what keeps him up at night are questions that include “how to reconstitute Jewish life amid the unraveling of American society and the moral bankruptcy of contemporary Zionism” and “how to build community in an age of widespread alienation and atomization.”

The book’s landscape is the American Jewish experience of the last century, starting in 1924, when Leifer’s great-grandmother Bessie arrived in New York. He describes the fast track from immigration to economic success and acceptance in American society that came at the price of wide scale assimilation and jettisoning Jewish education and observance. There were three pillars of consensus among American Jews during most of the 20th century, Leifer writes, the first being Americanism, the belief in the goodness of the U.S, and its offer of greater opportunities for a better life than in the old country. And it was true, as Jews have lived with more freedom in America than in any other diaspora in history.

The second pillar was Zionism, which became widely embraced after 1948, with Israeli statehood, and particularly after the Six-Day War of 1967, with Israel’s miraculous victory over three Arab states that had sought to destroy the world’s only Jewish one. American Jews felt that Israel and the U.S. shared democratic values, a belief that Leifer says led to “a moral myopia,” with Jews ignoring or supporting Israel’s growing nationalism and militarism, which he says includes its hardline and immoral treatment of Palestinians.

Liberalism was the third pillar, Leifer writes, and Jews flourished in a society that valued pluralism, individualism and volunteerism. But along the way, personal choice became more important than sacred obligation as Jews moved to the suburbs and, for the most part, lived middle-class lives with values very similar to those of their non-Jewish neighbors.

Speaking from a lonely place: Joshua Leifer is criticized by Zionists and fellow-progressives.

Jewish Culture In Decline

Throughout, Leifer doesn’t mince words in damning much of Jewish life today. He describes the present time as “the autumn of American Jewish culture,” with mainstream Jewish organizations increasingly irrelevant to young people, and “mainline affiliated Judaism sunken into indifference, satisfied with its shallowness and unaware of the extent of its own religious ignorance.”

One bright spot Leifer finds is in the emergence of new, alternative Jewish movements and initiatives, a number of which he describes, that are attracting young, liberal Jews with an energy missing in establishment synagogues. He would like to see such efforts replace Zionism as the core foundation for American Jewish life, but he worries that without a firm adherence to the commandments and serious study of Jewish texts, the benefits may not be sustainable.

Most surprisingly, Leifer devotes a lengthy chapter to what he calls “the Orthodox alternative,” namely the charedi, or ultra-Orthodox, world that he came to learn about first-hand from his wife’s large family in Lakewood, NJ. He is impressed with the warmth, religious commitment and chesed of these communities and asserts that while most branches of American Judaism are declining and becoming less relevant, this form of Orthodox life “will thrive long after the old mainstream institutions fade away.”

A charming section of the chapter is devoted to the yeshiva world, and specifically Lakewood’s Beth Medrash Govoha, the largest yeshiva in America, with 8,000 students, which makes it the second largest yeshiva in the world. The description of the huge main study hall, with the steady noise of hundreds of chavrutas (study partners), mostly in their 20s, employing “singsong argumentation” in reviewing the section of the Talmud they are learning, captures the fervor for Torah study that few outside the Orthodox world can imagine, much less experience.

But much of the success of the charedi world is its conscious separation from of the rest of the Jewish community – far from offering a model for Jewish unity. What’s glaringly missing in the book, is an in-depth look at the Modern Orthodox community that, even as it moves further right in ritual practice and politics, is seen by many as a potential bridge between the liberal and ultra-Orthodox branches of Judaism.

When I questioned Leifer about the omission, he acknowledged that it was unfortunate. He said he had written a whole chapter on Modern Orthodoxy, which he is well familiar with – he says he himself has taken “several steps to the right” in religious observance – but it was cut. That was done in part because dealing with the movement in a serious way would have been too detailed and technical for the readers he imagined would be interested in his book. “I was trying to appeal to NPR listeners,” he said. “I should have had an explanation” for why Modern Orthodoxy was missing.

Return To Jewish Values

Other serious issues I had with Leifer’s book include its lack of context about Israel’s motives for going to war and for its numerous attempts to make peace with the Arabs over nearly a century, each rejected other than the breakthroughs with Egypt and Jordan. The Six-Day War of 1967 was fought after Egypt’s President Nasser threatened to drive the Jews into the sea, but Leifer offers no reason for why “Israeli warplanes destroyed the Egyptian air force while it was still on the ground.”

The failed Camp David peace talks in the summer of 2000 are portrayed from the Palestinian point of view that the U.S. was not a fair mediator and that Israel was not serious about peace. But President Clinton and most objective analysts concluded that the PLO’s Yasir Arafat was the one not serious about peace. He never countered Israel’s generous offers and soon after, launched the Second Intifada, which lasted several years, resulting in many hundreds of Israeli men, women and children killed in scores of suicide bombings. That traumatic period hardened Israelis who had been enthusiastic about the chances for peace. Leifer’s lone comment in the book about the experience, that “naturally, this fear left its mark on communal politics,” is woefully inadequate.

There are other times when Leifer seems to describe historical events in ways that fit his narrative, like describing American Jewry’s communal legacy institutions in the latter part of the 20th century as right-wing. This misreading is primarily based on several outspoken leaders who were not representative of an American Jewish community that has been solidly liberal in its politics for almost a century.

There are more examples from this well-written and deeply researched book that are either misguided, naive or overly provocative. But what stood out for this reader is Leifer’s sincere attempt to call attention to the worrisome state of American Jewish life, which he says “has entered a period of dramatic uncertainty … at a time when the ground of communal life has begun to crack.” He would like to see a return to values that are grounded in Jewish tradition, law and text as well as progressive principles, a goal that seems far from realistic today.

In his recent Substack column, Leifer wrote that in his book and in his public writing and speaking, he tries to “walk the the line between connectedness and responsibility – between speaking to the people whose minds I want to change and combating the grievous harm in which my community, my people, are implicated. I know I have not always gotten it right. But that is one of the risks of thinking in public. We try. We fail. We try again.”

Agree or disagree with Leifer, his is a voice that should be heard.

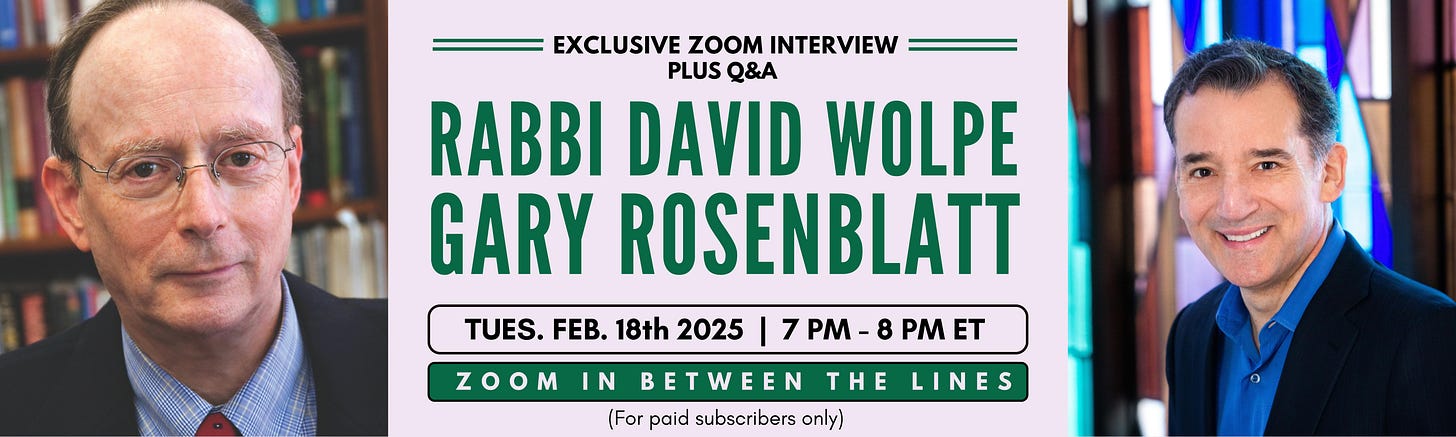

Attention free subscribers: Upgrade to paid in time to participate in this first of a series of exclusive Zoom interviews, February 18 at 7 pm ET.

Token Jews of the antisemitic far left aren’t serious people - they’re either grifters leveraging antizionism as a financial gain mechanism, or they’re narcissists who leverage the fact that legacy media is infested with the Free Palestine cult and spineless progressives, and tends to platform antizionist Jews because they themselves are antizionists and often token Jews. Leifer is both. The book makes him money and antizionists platform him, so he can Jew-wash their Judenhass.

Stop taking token Jews seriously. We have always had them. We survived the persecution of the communist Yevsektsiya Jews. We survived Labor Bundist Jews. In the end the far-left allies of the token Jews turn on them. The Yevsektsiya were purged to gulags and got shot in the head. Leifer hilariously was protested against by antizionists at his book promotion events. The point is to understand that they aren’t offering solutions, other than a genocide and ethnic cleansing for 7.7 million Israeli Jews. When people understand them as self promoting narcissists they can ignore their bullshit. Ironically American Jewish life has been reinvigorated by the virulent antisemitism of Leifer’s allies on the left and the vicious sadism of Leifer’s noble savage Pals.

"To our allies in Israel and to the Jewish people around the world, my message to you is this: Reinforcements are on the way”

—Senator John Thune, Nov 19, 2024

(now Senate Majority Leader)

Hope for the American Jewish community has been rekindled on Nov 5, 2024 and its enemies are in disarray. Happy Purim!

https://www.newsmax.com/world/globaltalk/john-thune-israel-democrats/2024/11/20/id/1188876/