Breathing Life Into A Community Given Up For Lost

Is there – should there be – a future for Polish Jewry? As the debate goes on, so does the effort to sustain it.

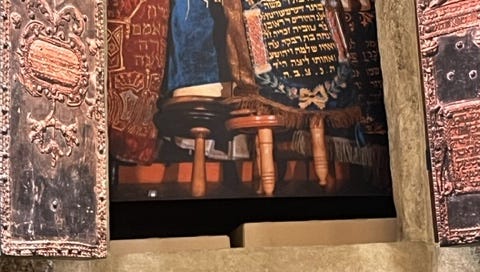

Inside the ark: The Torahs shown here, displayed in the famous Old Synagogue museum in Krakow, are a life-like portrait of real Torah scrolls.

The very last exhibit at Warsaw’s remarkable POLIN Museum of History of Polish Jews speaks to the ambivalent reality of Jewish life in the country today.

The post-modern structure, which opened in 2013, contains a multi-media experience covering the 1,000 years of Jewish life in a land where over the centuries Jews flourished, were persecuted and, during the Holocaust, almost completely extinguished.

My wife and I spent five absorbing hours traveling through time at the museum, built on site of the former Warsaw Ghetto. (We left when we did only because the museum was closing for the day.)

The final display features a large screen with videos of Polish Jews of all ages responding to the question of how they see themselves today. Some were close relatives of survivors, others were not. Some experienced anti-Semitism, others are far removed from Jewish life. Observing them after our day-long journey through the labyrinthine history of Polish Jewish life helped us better appreciate the wide range of their nuanced comments about their own Jewish identity, ranging from full acceptance to open rejection to everything in between.

The last and youngest to respond in the video, a smiling girl of about five, said simply, “I don’t know yet.”

The same could be said for many far older than her who face a conscious choice based on their family history, faith, fears and dreams of what the future holds for Jews and Jewish life in 21st century Poland.

Confront The Past, Assess The Future

We came to Poland to honor the memory of the millions of fellow Jews who were brutally murdered during the Holocaust and to try to absorb how such a barbaric, incomprehensible tragedy could happen in modern times. (For Part I of this two-part report, “Confronting Polish Jewry’s Tragic Past,” click HERE.) And we came to see what Jewish life was like today in a land written off by many as European Jewry’s graveyard.

What we encountered was a small but dedicated group of Jews committed to creating and sustaining an infrastructure and welcoming attitude toward those who may choose to join them. At the end of the piece I posted here last week, I noted that there are those “who are seeking to write a new chapter in the long-closed book of Polish Jewry.” In response, Konstanty Gebert, an author, educator and leading figure in the Polish Jewish community today, wrote to me: “The book of Polish Jewry was never closed: hands keep writing in it, even if only single sentences instead of entire chapters.”

His eloquent comment clashes with the views I’ve heard back home from those who feel that the very notion of building or maintaining Jewish life in Poland, a land soaked in Jewish blood, is an affront to the memory of those who perished there. Others are intrigued, wondering why any Jew would want to live in a country with such a dark history of oppression. But the reality is that even though the Germans murdered 90 percent of the estimated 3.5 million Jews who lived in Poland in 1939, the remainder – about 350,000 people – survived, and many stayed.

“We can’t change the number of Jews who were killed,” says Michael Schudrich, the Chief Rabbi of Poland, “but we can change the number of Jews who were lost.”

Opening the door: Michael Schudrich, Poland’s Chief Rabbi, is widely praised for all he has achieved in his three decades in the country.

Born, raised and ordained in New York, the rabbi, who is Orthodox, has lived in Poland for three decades. Based in Warsaw, he is spiritual leader of the Nozyk Synagogue, the only one of approximately 400 Jewish houses of worship in the capital that survived the bombings of World War II. In addition, he oversees the range of Jewish communal life in the country, including kashrut supervision, a Jewish day school in Warsaw with 250 students, and several Jewish community centers and synagogues.

“In the last 15 years there is more interest here in Jewish life,” the rabbi told me, noting that “at least a few times a month, I’ll be approached by someone saying they think a grandparent or other deceased relative was Jewish.”

How does he respond?

“My role as rabbi is to open the door to Yiddishkeit,” he says, “and there are 613 ways to enter. We teach Jewish values through mitzvot, we encourage and help people make their decisions on how they connect to Jewish life.

“They don’t have to be like me,” he adds, noting that the presence of Chabad and several Reform congregations in Warsaw “offers options for people and shows that there is vibrancy here. Our only obstacle is our will to help.”

Krakow: Few Jews and a Dynamic JCC

While no one knows how many Jews live in Poland today – or agrees on how to define that status – leaders of the community agree the number is growing. Not because more Jews are moving to Poland but because more people are coming forward to consider and explore their Jewish roots. Some surveys put the number of self-identified Jews in the country at 15,000, almost double the figure of a decade ago. But Jonathan Ornstein, a Queens, NY native who has lived in Poland for 21 years, insists “there are at least 100,000 Poles with one Jewish grandparent.

“We’re measuring the tip of the iceberg,” he believes, adding: “How can we not invest in trying to bring people back to Jewish life?”

Man with a mission: Jonathan Ornstein, CEO of Krakow’s JCC, says he wants American Jews “to see Poland not just through the lens of the Holocaust.”

Ornstein, the charismatic CEO of a remarkably active Krakow Jewish Community Center, is investing in the cause by creating a variety of educational and social services for the community. They include classes and workshops for children and adults, a new pre-school, and a popular four-day Ride For The Living bike ride from Auschwitz to Krakow that attracts participants from around the world. Since the war in Ukraine began more than a year ago, the JCC has committed major funds and manpower in support of Ukrainian immigrants.

As we entered the JCC building on a Tuesday afternoon, there was a long line of people stretching out into the street. We learned they were among the 400-500 people, primarily refugees from Ukraine, who come daily to receive packages from the food pantry the JCC operates every day of the year.

Ornstein has increased the JCC staff from 35 to 75 since the war began and estimates that “we’ve helped more than 200,000 Ukrainians” during that time in Krakow and inside Ukraine. In addition to providing free food, the JCC offers medicine, clothing, toys, language classes, psychological help and rent-free apartments to those who require housing.

“We decided on Day One of the war that, together with other Jewish organizations, we would do all we can to help Jews and non-Jews equally,” Ornstein said. More than 98 percent of Ukrainians who have received support from the JCC are not Jewish.

To meet these needs, Ornstein says he has been spending half his time in the U.S. raising funds. “We’ve provided more than $10 million worth of direct support to Ukraine so far, thanks to 4,000 individual donors as well as foundations, synagogues and Jewish federations.”

(UJA-Federation of New York is one of the leading funders.)

With it all, Krakow still has a very small Jewish community, no day school and limited kosher food. It does have a Jewish district, Kazimierz, that dates back to the 15th century. Jewish life flourished there at times; Rabbi Moshe Isserles, a leading 16th century scholar known widely as The Remah, had a synagogue there that has been reconstructed and is still used for prayer. At other times, the Jewish community of Kazimierz was cut off from the rest of the city.

We visited the charming town square, with Jewish-themed shops, lodgings (Hotel Rubenstein, for example.) and non-kosher restaurants advertised with Hebrew lettering. But the area is, in effect, a Potemkin Village, a facade that disguises the fact that virtually no Jews live there.

Most notable, though, was the aptly named Old Synagogue, dating back to the 15th century, whose history mirrors much of Polish Jewry. The oldest synagogue still standing in Poland, it was the center of Jewish activity and prayer in Krakow until it was destroyed, ransacked and looted by the Germans in World War II, and is today a museum, no longer a house of prayer.

A close look at the open ark reveals that the Torahs inside are not real but rather an artfully painted representation.

Passive Outreach

While the Jewish district may be less than what it seems, there are dedicated activists promoting Jewish communal activity in Krakow.

An Orthodox rabbi, Avi Baumol, a native New Yorker with a wife and five children in Efrat, a West Bank community in Israel, spends two weeks a month in Krakow, based at the JCC. He makes a point of wearing his kippah in public and attracts people who seek him out, often to reveal that they are looking into their own, or suspected, Jewish heritage.

“We’re very open and inclusive,” he says.

Like Rabbi Schudrich, he practices a kind of passive outreach, making himself available for conversations that sometimes lead to study classes in Jewish texts with him, and occasionally to conversions, which are handled by Orthodox rabbinic courts in Jerusalem and major cities in Europe.

Most who identify Jewishly in Poland do so culturally and communally rather than through ritual observance, and the majority are not halachially Jewish. It’s rare to meet a young Pole with two Jewish parents. Far more common is encountering community members who were told – or discovered – they were Jewish as a teen, or older. Sometimes an elderly grandparent, or a death certificate or other document, will reveal the long-held secret.

That’s because being identified as Jewish presented a serious risk, and as a result of the tragedy and chaos of World War II, many survivors decided not to place that burden on their offspring.

Outreach to the young: Mariia Hershova (left) and Klementyna Pozmiak of Hillel in Krakow.

Klementyna Pozmiak is director of the Hillel in Krakow, founded in 2017. Now in her 20s, she said she was 12, living in Cleveland with her Polish immigrant parents, when she found out she was Jewish. “My mother’s mother had two sets of dishes, and a menorah was found at home.”

A year later she had a bat mitzvah and read from the Torah, thanks in large part to her preparatory study with a kindly neighbor, a Holocaust survivor who lost his family at Auschwitz,

“He became like a grandfather to me,” Pozmiak said.

She came back to Krakow in 2014, and settled there three years later. Pozmiak and her close friend and associate, Mariia Hershova, conduct Hillel-sponsored programs for about 50 people between the ages of 18 and 35, emphasizing Jewish culture and community.

Hershova, a native of central Ukraine who has lived in Krakow for five years, focuses her Hillel work on Ukrainian Jews, most of whom came to Poland with their families.

The two women host kosher Shabbat dinners for up to 30 guests in their small office on a regular basis and “get to know people and their stories on a personal level,” Hershova said. “We try to create a comfortable environment and not push too hard. It takes time.”

The Truth Cannot Be Buried

Over the course of our week in Poland, we came to appreciate that many of the most dedicated volunteers and professionals at Jewish museums, community centers and archives, and as tour guides at concentration camps, were non-Jewish Poles.

Each had their own reasons. They were too young to feel a direct sense of guilt for the possible actions of long-deceased relatives. But they often expressed a sense of moral responsibility to honor the memory of millions of people murdered simply because of their religion. Several mentioned having an older relative with an interest in Jewish life.

Is it possible that person was Jewish?

Guiding light: Malgorzata Smreczak, education specialist at The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, wants young people to apply the lessons of the past.

Malgorzata Smreczak, who is in her late 20s was our guide at The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, one of the most powerful experiences of our stay. She grew up interested in Jewish culture. She said her father is not Jewish but she wasn’t sure about her mother’s family.

A book she read as a young girl about women victims at the Majdanek concentration camp made a memorable impression on Smreczak. During law school, she was a guide at Majdanek. After studying law for five years, she said she found more meaning in Jewish history and is now finishing a master’s degree in the field.

As educational specialist at the Institute, she often gives tours to Polish students, relating the poignant story of how Ringelblum, a young social worker, political activist and historian at the Institute in the 1930s, organized a secret group – known as Oneg Shabbos – of about 50 to 60 contemporaries in the Warsaw Ghetto. He urged them to keep diaries and save photos and artifacts to provide an accurate description of the horrific events taking place in the Ghetto – of life and death under the German occupation.

“I want young people to know of what happened then,” Smreczak said, “and to know it is happening again near our border” with Ukraine.

The Oneg Shabbos participants placed thousands of pages of material in metal containers and two large milk cans and buried them. Their hope was that the archives would be found after the war and inform the world of what took place — and help in the prosecution of war crimes against the Germans.

Preserving the past: One of two milk cans containing thousands of pages of archival proof of life and death in the Warsaw Ghetto was found in the rubble years later. It is housed in the Ringelblum Institute. The other is in the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

Ringelblum and his family, and all but three of the secret group, perished, but miraculously, the buried material was found in the rubble of the Ghetto. Those archives form the core of the Institute’s exhibit.

An award-winning book by Samuel Kassow, “Who Will Write Our History” (2007) and a semi-documentary film by Roberta Grossman with the same title (2018), tell the inspirational story of how the truth was preserved, ensuring that future generations can bear witness to the tragic past.

Today, the question of who will write our history can be applied to the Jews of 21st century Poland.

Is there, indeed, another chapter to be written?

The jury is out, but as Jonathan Ornstein of the Krakow JCC asserts, “no community is ever beyond hope.”

A Final Thought

Ornstein’s comment came back to me during our Shabbat in Warsaw.

We attended the majestic Nozyk Synagogue, built at the turn of the 20th century, when Warsaw had the largest Jewish population of any city in the world. Throughout the year, several dozen people attend Shabbat services, but this weekend the synagogue was host to hundreds of students from around the world, participants in the March of the Living program.

On Friday evening and Shabbat morning, the synagogue’s 600 seats were filled to capacity, as were the aisles where young people stood – and danced. There was a proud, celebratory spirit as the students sang “Am Yisrael Chai,” the people of Israel live.

In a day or so, their time in Poland, anchored by their visit to Auschwitz, would be over. They would be flying to Israel to mark Israel Memorial Day and celebrate Israel Independence Day.

From darkness to light, from death to rebirth.

And what of those Polish Jews who remain behind?

Equally moving for my wife and me as the Friday evening and Shabbat morning services was the low-key afternoon Mincha service, followed by the traditional third Shabbat meal, attended by the local “regulars” and a few visitors. The big crowd was gone, but this felt authentic, a glimpse of the day-to-day reality for those in the community clinging to Jewish life.

As we sat around the tables in a synagogue that once knew glory, was abandoned and then reclaimed, we sang “Mizmor L’David,” the 23rd Psalm traditionally sung as Shabbat wanes. Its words took on new meaning for me: “Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for you are with me.”

Indeed, “no community is ever beyond hope.”

Note:

I welcome your comments, as always, and plan to post some of the thoughtful responses I’ve received to Part I and, hopefully, to this report on Polish Jewry, in the next few days.

If you do comment, or have already done so, please indicate whether or not you’d like me to include your name. I won’t include your name without your permission.

Many thanks.

This was a very meaningful post, Gary. It brought back memories of the trip Bernie and I had to Krakow in 2006. We were accompanied by a Jewish Studies faculty member at Jagiellonian University. I think she was Jewish, but in any case, we were impressed that there were, at the time, around 20 professors in that department. As you noted, Kazimierz was fascinating...non-kosher restaurants where you could get Jewish foods related to every holiday on the calendar, all at once! I took a particular interest in the Isserles shul, as I have a document claiming that I am descended from the Remah. I recall standing at his grave and telling him, aloud, that I am back, and that we Jews are still here. And of course, we learned that the annual Jewish music festival features non-Jewish performers. Even though I think the Polish government pursues connection with Jews because it brings in tourists, I am glad that Jewish life continues there. Hitler did not win after all.

The apparent large number of people discovering/suspecting Jewish ancestry reminds me of those in the American Southwest & in So. America who are discovering/suspecting ancestry from the Crypto-Jews of the Inquisition.