Bringing The Hidden Into Focus

Photographer and activist Joan Roth has spent more than five decades making women here and around the world visible

On a mission: The camera ‘gave me a greater purpose in life,’ says Joan Roth.

Joan Roth spent much of last Saturday taking photos at New York City’s annual Dyke March downtown and says she came home “exhausted.” But on Saturday night, she asked me if we could move up our scheduled Zoom interview for the next day to 8 a.m. so she could be on hand to photograph the city’s annual Pride March down Fifth Avenue well before its scheduled 11 a.m. start.

When I asked Roth, who turns 81 this summer, what drives her to continue this pace of activity in her sixth decade of an illustrious photography career, she laughed and said, “I can’t believe I’m doing it and I can’t tell you what it is, but it’s been this way since the beginning.”

Roth grew up as a shy girl in suburban Detroit, “afraid to go anywhere myself.” She says the camera has been the instrument that “gave me a greater purpose in life.” It has allowed her to travel the world, often in remote and sometimes dangerous surroundings, on a journey of both self-exploration and compassion for others. It has “enabled me to go beyond myself, to enter the lives of people I would not have been able to meet otherwise,” she said, “and to know people in a deep way.”

Most of those people have been women – from “shopping bag ladies” living on the streets of New York to national feminist icons to Jewish women in some of the most exotic regions of the world where Jewish life is becoming extinct.

Roth says she doesn’t think of the women she photographs as subjects but rather as teachers and often, in the end, friends.

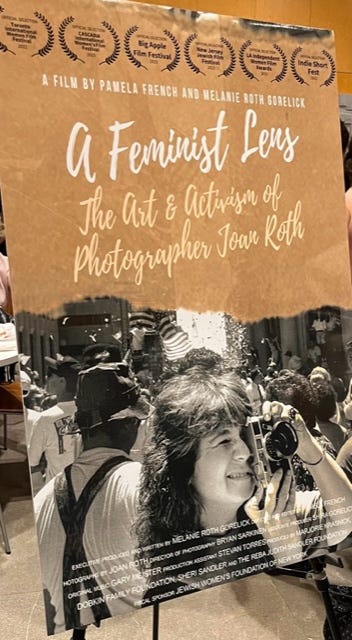

That outlook helps explain the extraordinary range, depth and empathy in Roth’s work since the 1970s, which has been exhibited in major exhibitions around the world, published in books, and now is the focus of a new, 30-minute documentary, “A Feminist Lens: The Art and Activism of Photographer Joan Roth.”

A showing of the film at the Marlene Meyerson JCC Manhattan last Tuesday night for a standing-room-only crowd of more than 200 enthusiastic devotees of Roth and her mission – followed by a panel discussion that included her, her daughter and filmmaker granddaughter – became a joyful celebration of Jewish feminism.

Roth at work: Poster promoting the new film on Roth’s life and career.

Among those attending were Dr. Delois Blakely, a Harlem-based advocate against homelessness who calls herself “Queen Mother,” Gloria Steinem, a co-founder and national leader of the feminist movement, and Rabbi Sally Priesand, the first American woman ordained to the rabbinate, whose portrait by Roth for the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. will be exhibited there this fall.

Another first: A print of Roth’s photograph of Sally Priesand, the first female rabbi in the U.S., will be exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. this fall. The Hebrew letters spell “avodah” (service, or worship).

Steinem spoke briefly at the outset of the evening, praising Roth as a caring friend and key figure in telling women’s stories. “Joan sees the humanity in people who might not be considered important or worthwhile in the eyes of many,” she observed in the film. “She enlarges our human family and our ability to empathize.

“Making women visible,” she added, “is a step toward bettering the lives of women everywhere and that's a step toward the creation of democracy.”

The ‘Shopping Bag Ladies’

Roth, 80, is a pixie-ish woman with an open smile and white curly hair whose gentle, modest manner belies her fierce commitment to her vocation, and to many of the women she has photographed — perhaps most notably, to some of the first homeless women she met in the early 1970s. They were the “shopping bag ladies” of New York City, and while others looked away, Roth approached, got to know and befriended a number of these women, often bringing them food, clothing and money. With their permission, she photographed them.

Her first encounter was with a woman, who turned out to be Jewish, camped out on the Upper East Side across the street from where Roth lived. She called herself Sonia, Sofia, Mary, Ellen, Barbara, and wore clothes held together with safety pins. Another was a woman named Maggie, who lived in Central Park.

Roth said she was shocked at how they lived and wanted to know what had happened to these women.

And as a single mother of two daughters, she worried that she, too, could end up homeless.

Sonia, Sophia, Mary, Ellen, Barbara …. those were the names this woman used. She was the first homeless woman Roth got to know.

Maggie lived in Central Park until Roth helped her relocate to a place in Long Island City.

‘Queen Mother’ Delois Blakely and Roth have been fighting efforts to evict black women from Harlem apartments for many years.

Her black and white photos of New York homeless women, accompanied by their stories, were published in Ms. magazine in 1977, and resulted in a book, published five years later, titled “The Shopping Bag Ladies of New York.”

Though many of Roth’s friends were upset that she made the issue her cause, her active involvement led to finding a place to live in Long Island City for Maggie, and her advocacy with housing authorities resulted in the city expanding its services and shelters for homeless women.

The 1970s was also a time when the feminist movement was gaining recognition and energy, and Roth wanted to be a part of it. She photographed rallies in New York and Washington, and in 1977, attended the National Women’s Conference along with 20,000 other women. Her photo of feminist icon and former Congresswoman Bella Abzug, who presided at the gathering, handing over the torch to First Ladies Lady Bird Johnson, Rosalynn Carter and Betty Ford, captured the zeitgeist of the feminist era.

Passing the torch: Feminist leader and former Congresswoman Bella Abzug at the National Women’s Conference in Houston, 1977, with First Ladies Lady Bird Johnson, Rosalynn Carter, and Betty Ford. Twenty-thousand women were in attendance.

‘I Had To Go’ To Ethiopia

During this time, Roth, who grew up in an observant home, became more involved in Jewish life. She began publishing photos in Lilith, the Jewish feminist magazine in the late 1970s. Editor-in-Chief Susan Weidman Schneider, who moderated the panel discussion at the JCC last week, says Roth’s photos – and her remarkable career – help women see things in a fresh perspective. “Joan opens the aperture bigger,” she said, “so you can see the possibilities.”

Over the years Roth worked with Project Kesher, which develops women’s leadership in Eastern European countries; Jewish Women’s Archives; Hebrew-Union College; and The Jewish Week, where I first met her in the mid-1990s. As editor, I would see her, camera in hand, at many Jewish events. She was warm, friendly and spirited, and I greatly admired her work. But I was unaware of the scope of her accomplishments as an activist and advocate beyond her photography.

Roth joined and took classes at the Carlebach Shul on the Upper West Side, led by the charismatic chasidic singing rabbi, Shlomo Carlebach. She said the experience made her feel more spiritually attuned to her Judaism

In 1984, Roth was at a Shabbat dinner in New York when someone mentioned the plight of Ethiopian Jews seeking to live in Israel. “I didn’t know anything about them but I decided I had to go,” Roth told me. She joined a Jewish volunteer effort and spent two weeks in an Ethiopian village, forging an instant friendship that continues to this day with the beautiful young wife of the rabbi.

“Her name is Abbae, and she was carrying a baby when she came up to me and said, ‘My sister, my sister,’ and took me by the hand to her home. It was extraordinary. The whole trip was extraordinary.”

One of Roth’s favorite photos is of Abbae looking into the camera while nursing her baby. “She said she wanted me to take it in case she didn’t make it out of the country,” Roth explained, “and she wanted people to know of life there.”

Ethiopia 1984: Abbae was the wife of the rabbi in an Ethiopian village. Now a widowed mother of seven children, with many grandchildren, she lives in Ashdod, Israel, where Roth still visits.

Roth made three arduous trips to visit with Ethiopian Jews in 1984 and 1985, and over the next dozen years made more than 40 visits to photograph Jewish women around the world – largely at her own expense. She said she never received Jewish communal support for documenting foreign Jewish communities as some male photographers later did. But there is no bitterness in her voice. “It was hard for me as a woman and I never did it for the money,” she said.

What prompted this adventure/obsession?

Roth said she was simply “drawn to Jewish women, all of whom are extraordinary,” and she identified with the deep commitment to the rituals of “keeping Shabbat and baking challah and cooking” that she found among women in places where Jewish life was disappearing, like Ethiopia, Bukhara, Ukraine, India, Eastern Europe, Russia, Yemen and Morocco.

Roth also mentioned that she never met her paternal grandmother and found that in visiting distant Jewish communities, “I wanted to find my grandmother, and myself. And now I’m beginning to.”

A scene from the Bible? Yemenite women cooking.

Jewish marriage, Yemen-style: Two wives of the same man in a remote mountain village Roth visited in the 1990s. She said she stayed overnight and observed that after dinner, when the husband chose the wife to be with that night, the other wife cried. Why was Roth there? ‘I must have been insane,” she says, laughing.

‘You Have To Give Up A Lot’

Roth’s Bohemian lifestyle as a single parent with limited funds, managing to fly around the world to exotic settings, put a strain on Roth’s relationships at home, she acknowledges. There were times when “everyone hated me for doing this, and friends stopped talking to me,” but she felt a deep inner need, as if on a mission.

“I never knew what I was doing, I just did it. It was unfortunate for my children. You have to be dedicated, and you have to give up a lot,” she said, adding: “I wouldn’t do it today.”

Roth’s daughter, Melanie Roth Gorelick, recalled how she and her sister, Alison, grew up in a city apartment that gradually became their mother’s photo studio. “She had little money, and gave up the living room furniture and made the kitchen into a dark room. We were all supposed to live for her photography.

“It was a hard time,” she said, “but it was clear that this was her calling.” It was a combination of “personal, political and spiritual” that drove her mother, and “spiritual is where she needed to be.”

Roth Gorelick said her mother took her and her sister to women’s rallies and events and instilled in them a consciousness about women’s issues and homelessness. She and her mother shared a common interest in empowering women, with Roth Gorelick working the 1990s with the United Nations Development for Women [now UN Women], and mother and daughter attending the fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, China in 1995.

It was during the pandemic, when she moved in with her mother, that Roth Gorelick came up with the idea of preserving her mother’s story. “Covid changed our relationship,” she said, as her appreciation for her mother’s life work deepened during the time they spent together.

She enlisted her close friend, Pamela French, a producer, director and editor, to do a series of interviews with Roth over a period of two days. “Mom and her stories came alive when she told them, and I learned a lot,” Roth Gorelick said. It led her to conceive of the film as part of a legacy project to protect and catalogue her mother’s work.

Roth Gorelick, a longtime Jewish communal professional, wrote and served as executive producer of the film. “As a proud daughter, I felt my mother deserved more acclaim” for the full range of her work, from the photography to the activism that still has her lobbying in Albany for the homeless.

Roth was wary at first of the attention the film would bring, more comfortable focusing on others than on herself. But as it has been shown in film festivals, she is getting used to the attention. And grateful that she is still able to pursue her life’s mission.

“Every new photo I take is my favorite,” she says with a smile.

For a link to the trailer for the film, “A Feminist Lens: The Art and Activism of Photographer Joan Roth,” click HERE.

What an extraordinary woman, a privilege to call her a friend...wonderful to see her getting the accolades long overdue!!