Israel Already Has A Blueprint For A Constitution

A remarkable covenant was co-authored by a prominent Orthodox rabbi and avowedly secular legal scholar 20 years ago. What came of it? Can it be revived today?

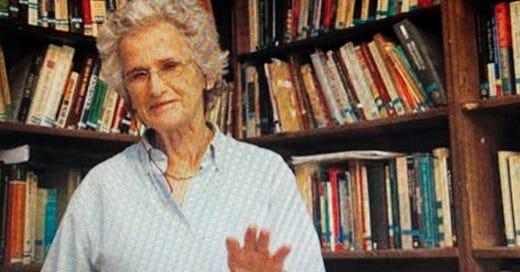

The Professor: An advocate for “the common ground,” Ruth Gavison was rejected as a High Court nominee by Chief Justice Aharon Barak in 2005, reportedly because she was critical of judicial activism.

The Rosh Yeshiva: Rav Yaakov Medan was criticized by some rabbinic colleagues as being too lenient in his views on religious-secular issues in the covenant.

Seventy-five years ago, at the birth of the State of Israel, the fledgling government pledged to produce a Constitution within five months.

It never happened.

For reasons why, read on.

But the more urgent question is whether it is still possible to produce a binding social contract that would address – and help resolve – some of the major conflicts that have led to the greatest domestic trauma in Israel’s history.

Many legal experts insist the current crises over issues including religion-state conflict, defining the nature of the state, and the need for checks and balances, are rooted in the lack of a Constitution that puts forth clear boundaries and is acknowledged as the primary law of the state.

Asserting that “democratic Israel … is in danger of collapse,” Sharon Roffe Ofir, an academic and former member of Knesset, wrote in The Jerusalem Post last week that “the time is ripe to put a solution on the table” that would “lay out the rules of the game and fix the broken ties between us.”

Her essay is a timely and thoughtful argument for the need for a new Constitution. But it makes no mention of a little-known social experiment that paired two highly unlikely partners in dialogue. Theirs was an attempt to resolve the oldest, thorniest – and now most urgent – element of Israeli societal conflict: the clash between religion and state.

Seeking ‘A Common Ground’

Ruth Gavison, a recipient of the Israel Prize, was a distinguished Hebrew University professor of law, and an avowedly secular expert on, and fierce advocate for, human rights. Rav Yaakov Medan, who fought on the Golan in the Yom Kippur War, is a Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Har Etzion in the settlement of Gush Etzion, and a leader in the Religious Zionist movement.

The professor and the rabbi, who had not met before, disagreed on almost every issue. But motivated by the ugly aftermath of the Rabin assassination in 1995, they shared a common belief that their work was crucial to Israel’s societal future. And they believed that the key to creating a new “status quo” in bridging Israel’s religious-secular divide was to find ways for both communities to live together by honoring what unites them rather than deciding in favor of one or the other.

The project, begun in 1999 with the support of the Israel Democracy Institute (IDI), Shalom Hartman Institute and Avi Chai Foundation, is known as The Gavison-Medan Covenant. It is a social contract based on creating “a common ground … that must prevail over our differences.” Dealing with issues of personal status and religious practice, the covenant asserts that “it is possible to arrive at a single joint proposal without contradicting the tenets of our divergent beliefs: the Torah and Jewish law on the one hand, and the centrality of the principles of equality and human dignity and liberty on the other.”

For example, the covenant calls for a two-tiered marriage registration system, with each couple first obtaining a marriage license from a civil authority and then free to opt for a religious ceremony through any of several organized religious communities.

In addition, no one group would have a monopoly on dictating religious norms like dietary laws, Shabbat, prayer services or burial. Every group would have the right “to preserve its own lifestyle according to its own conceptions and interpretation.”

A key element for success would be preserving the covenant in law, giving “preferences to mechanisms for negotiation and compromise” and not allowing the courts to invalidate its content.

Professor Gavison and Rav Medan spent three years working together and published a detailed document in 2003 of more than 100 pages, in Hebrew and English, published by Avi Chai and the IDI. It was met with quite a bit of enthusiasm among some scholars, but no legislation based on the covenant has ever been passed in the Knesset.

Professor Gavison died in 2020 at the age of 75.

I spoke with Rav Medan after Prof. Gavison’s death, and he said that while she was a fierce advocate for liberal values and human rights, “she understood and could work with others” of all beliefs and backgrounds. He said he greatly admired her courage and convictions and that her death was “a grave loss for Israeli society.”

What Impact Did The Covenant Have?

The Gavison-Medan Covenant was one of many attempts by various organizations, foundations and academics to grapple with the lack of a Constitution in Israel. The IDI, an independent research and action center in Jerusalem, spent years devoted to the issue.

There are several reasons given for why the initial effort to establish a Constitution in the early days of statehood failed. In part, with the tiny state at war from its first day of independence, and with a Declaration of Independence providing guidance for a new legislature, there was a sense that the contentious and time-consuming work required in creating a Constitution dealing with personal status issues – like the Law of Return, conversion, marriage and Shabbat – could be postponed. Founding Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion believed that many in the diaspora would settle in Israel in its first decade of statehood and that it would be best to wait until the population grew to include a wider range of Jews.

A more pragmatic theory is that the religion-state issue was really about power, and that the political parties that had it were not anxious to negotiate with those who didn’t. And some believe the Orthodox parties continue to oppose a Constitution because they fear it would be based on democratic rather than Torah principles and values.

But attempts to explore and resolve the issue continue. Just this week former finance minister and current Yisrael Beytenu chair Avigdor Liberman asserted that “religion and state must be separated; this is the most urgent and necessary thing.”

Last fall, a two-day conference in Jerusalem focused primarily on whether the Gavison-Medan Covenant is relevant today, 20 years after it was published.

Shlomit Ravitsky Tur-Paz, a former IDF commander who co-founded and co-directed The Itim Center, which promotes Jewish pluralism and culture, played a key role in the conference, which included discussion of the covenant’s successes and failures. She noted that the document has become a kind of marker on how to approach the conflict and it succeeded in showing that a spirit of give-and-take, even on the most contentious of issues, can lead to compromise and consensus when there is trust between the discussants.

“The obvious failure was that the covenant did not result in any legislation,” she told me this week. In addition, some say it was a mistake for Prof. Gavison and Rav Medan not to have widened their efforts to gain support by including other colleagues, politicians and organizations sympathetic to their efforts.

Ravitsky Tur-Paz believes that efforts by the current government to push through rigid religious laws on personal status issues only alienates traditional and secular Jews and drives them farther apart from Judaism. “Belief, and a bond to culture, tradition, and history cannot be achieved by compulsion, but only through love,” she has written.

Her words echoed comments I heard Prof. Gavison make at a program on “Judaism and Women’s Equality” in Israel in 2013. Asserting that no social or legal changes regarding women’s rights in Israel are possible unless religious leaders endorse (or at least not oppose) them, she made the case that social pressure from the outside can prod rabbinic authorities to make internal accommodations to halacha (Jewish law).

“Halacha is the creation of the tradition,” she explained. “The only way to change halacha is through the social process, and the legal, from within halacha,” when religious leaders see that society cannot live with the status quo.

“It’s a fascinating internal struggle that takes place within halacha,” she added. “We must facilitate, not coerce. And we must be patient”.

Needless to say, there is precious little patience today among those coalition legislators who would compel the majority of Israeli society to adhere to the most stringent application of religious laws. And the notion of opposing leaders debating – based on mutual trust and concern for consensus – on a range of vital political and religious issues is, sad to say, beyond the realm of imagination.

“There is no one carrying the cause today,” observed Steven Bayme, a former executive of AJC, which published a series of articles on the Gavison-Medan Covenant about 15 years ago. “Had there been more desire to cooperate at that time,” he mused, “it might have been a great corrective.”

Note: Several passages describing the Gavison-Medan Covenant appeared in a Jewish Week “Appreciation” I wrote of Prof. Gavison after her death in August 2020.

I never heard of this covenant. Fascinating and sad that the opportunity was lost. Is it possible to take a step back to that time before moving ahead?