Remembering Isi Leibler, Who Spoke Out When Few Would Listen

A major new biography highlights the impact one man had, from international politics to intra-Jewish infighting.

A compelling biography of a feisty advocate for Israel, the Jewish people and ethical standards.

Some people make their mark in Jewish history by heading a major organization and championing an important cause. Others gain recognition as whistleblowers, calling out wrongdoings within a group and striving to restore ethical behavior and policies despite powerful resistance.

Isi Leibler, who died at 86 in Jerusalem on April 13, was unique in that he was both – an outspoken establishment leader and, as a man of conscience, someone willing to expose corruption, even within groups where he held top posts.

He was bright, opinionated, feisty and never one to back down from a challenge. We had our differences at times, particularly during the Trump years. But I count myself among Isi’s longtime admirers, having worked closely with him over a period of several years in reporting extensively on two major stories. Both of his initiatives were focused on bringing more transparency to well-respected international Jewish organizations where he was serving in top lay positions. In both instances he found out along the way that there were serious financial and other problems that needed to be addressed, and he pursued them, despite major pushback and threats.

Accounts of these major confrontations with the World Jewish Congress (WJC) and the Conference on Material Claims Against Germany – better known as the Claims Conference, the Jewish group which deals with Germany in seeking compensation for Holocaust victims – take up more than 70 pages of an important biography of Isi that was published a few months ago.

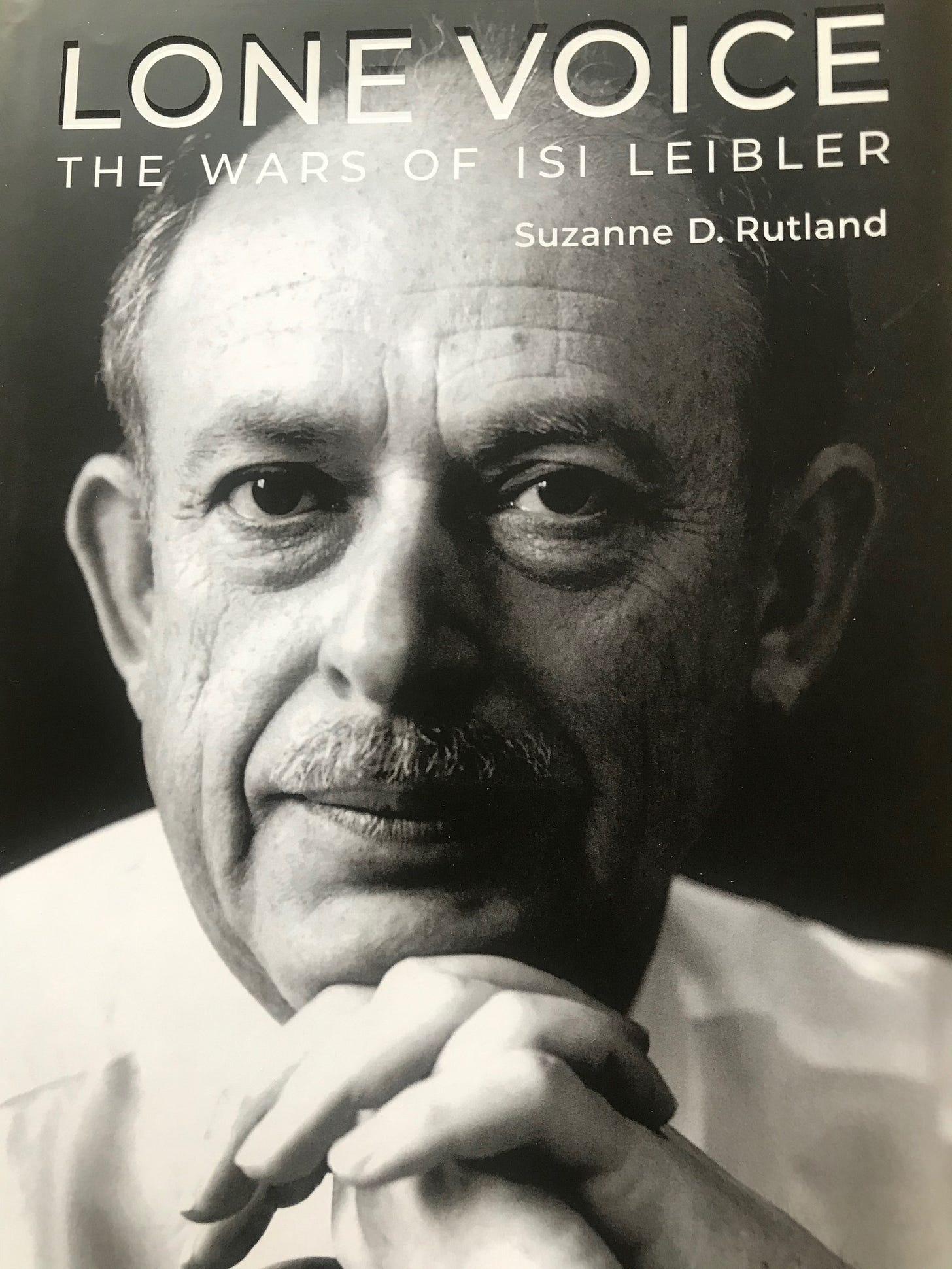

Entitled “Lone Voice: The Wars of Isi Leibler,” it is a majestic piece of history from Suzanne D. Rutland, a highly respected Australian Jewish historian. She spent two decades researching and writing this compelling and carefully documented work, with extensive footnotes on almost all of its 650 pages.

The book describes the life and career of a man who, in addition to being highly successful in business, played an outsized role in Jewish communal life for more than six decades. Born in Antwerp, he moved to Melbourne with his family when he was five. He served three terms as president of the Executive Council Australian Jewry and chaired the WJC governing board before his aliyah in 1999 to Jerusalem, where he became a widely read and highly opinionated columnist in The Jerusalem Post.

Rutland sheds light on both the global diplomatic front, where Isi was instrumental in establishing ties between Israel and China and India, and the sometimes brutal backroom politics he became embroiled in within influential Jewish organizations.

There is a measure of comfort in knowing that Isi lived to see the publication of the book and the favorable reviews that followed. The last several times we spoke, he glossed over his serious medical issues and focused on recounting some of our shared “battles” in taking on some powerful adversaries.

No doubt Isi will best be remembered as an early and influential advocate for Soviet Jewry, which included traveling to the USSR and meeting with refuseniks. He is credited with being among the few who made the issue into an international cause in the 1960s, bucking the establishment Jewish community’s preference for quiet diplomacy by advocating public protests and rallies.

I knew him best, though, after the remarkable success of the Soviet Jewry movement. We began to meet for breakfast in Manhattan once or twice a year in the early 2000s, when Isi chaired the governing board of the WJC and would travel from his home in Israel to the U.S.

Edgar Bronfman was the head and chief financial backer of the group, and his top professional and close confidant was Israel Singer.

As Isi became more involved in the workings of the WJC, he sought to apply standard business practices and democratic methods, which Singer resisted strongly. And with good cause, it turned out, because he was found to have a secret Swiss bank account, and millions of WJC dollars were unaccounted for.

Isi would share with me some of his troubling findings about the WJC and put me on the trail of others who were privy to damaging information. He recognized that press coverage in The Jewish Week could galvanize a public outcry against the WJC’s elaborate cover-up. Based in large part on the factual information that Isi provided, the paper published a number of editorials and news stories raising questions about how the WJC operated.

Over time, the general press here and in Europe also covered the brewing scandal, which resulted in the New York State Attorney General’s office issuing a legal filing critical of the WJC. Israel Singer’s financial escapades were curtailed and Isi’s allegations of lack of oversight were borne out.

But it took several years for the drama to play out fully, and along the way, the WJC in Israel sued Isi for $6 million dollars for defamation. The Jewish Week and several European Jewish publications were threatened as well.

Isi had been removed from power at WJC during this time, but he waged a strong legal and public relations defense as more revelations about Singer’s financial improprieties came to light. Without fanfare, the WJC finally withdrew its libel case against Isi.

In March 2007, Edgar Bronfman, recognizing that he had been betrayed by Singer, whom he later described as “the man I called my rabbi, my friend and even my son,” fired him.

These events closed a sad chapter in the proud history of the WJC. But while Singer became persona non grata there, he remained president of the Claims Conference and chair of the World Jewish Restitution Organization, which pursued claims for recovery of Jewish property in much of Europe.

Ever the maverick, Isi, now speaking out primarily through his opinion column in The Jerusalem Post, called for reform at the Conference. He advocated for new leadership, asserting that aging survivors were not being helped sufficiently and that funds were being diverted for non-Holocaust related causes.

The chorus of critics grew when it was learned in 2010 that at least $42 million set aside for survivors had been stolen from the Claims Conference through an elaborate scam by a group of its employees over a period of years.

But the leadership fought back and went on offense, accusing Isi of being a vindictive “scandal monger” and worse. They managed to hold on to the reins, though some employees were prosecuted and convicted.

Reading Rutland’s biography and recalling the details of those fierce conflicts, it became even more clear to me why her title for the book, “Lone Voice,” was so appropriate. As was the subtitle, “the wars of Isi Leibler,” whose battles ranged from decrying the anti-Semitic Kremlin to resisting efforts to squelch his criticism emanating from the very organizations so dear to him.

Isi was a leader, and his compass was consistently pointed toward justice. We need more like him. May his memory be for a blessing.

Smart tribute column.