Ruth's Conversion Would Be Rejected Today

On the eve of Shavuot, a reminder of how far Israel's Chief Rabbinate has come from the spirit of the festival.

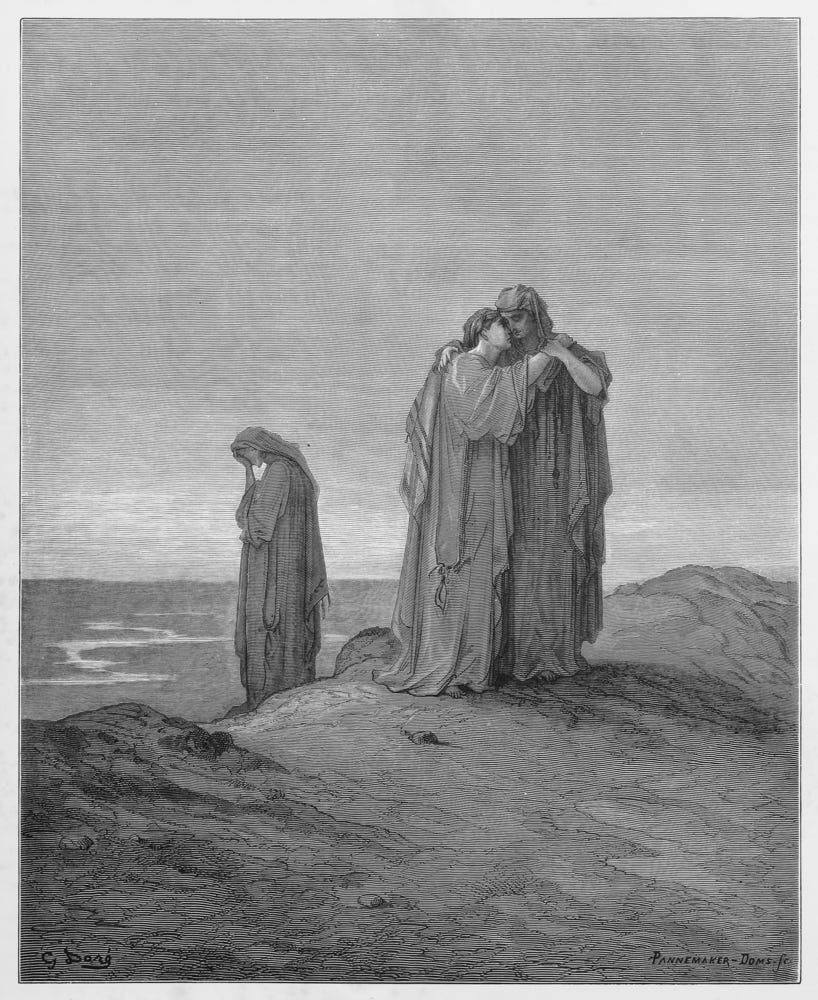

A timeless pledge: “Your people shall be my people….your God my God,” Ruth said to her mother-in-law, Naomi.

At a time of frighteningly deep divisions within the Jewish community on issues from religious practice to the policies of the State of Israel, we are about to celebrate the festival of Shavuot, the Feast of Weeks, identified with the most unifying theme in Jewish life: receiving the Torah, the central, foundational text of our history and people, at Mount Sinai.

All the more sad, then, that Shavuot, which falls this year on Thursday evening, Friday and Shabbat, is the least celebrated of the three major festivals. It has no seder to observe like Passover or sukkah to sit in like Sukkot. Many American Jews could not tell you what Shavuot is all about. Something to do with the harvest in ancient times or eating cheese blintzes today.

But this holiday gives us the story of one of the most endearing characters in our literature, Ruth, the gentle young Moabite widow who rejects her past and casts her fate — and shapes ours — by embracing Judaism.

A closer look at the story of the most famous convert in Jewish history offers up a timely message about how we can approach the dangerous fissures in Jewish life today in a way that can help us heal and bring us closer together. In so doing, it presents a stinging challenge to the dangerously narrow interpretation of conversion laws in Israel today and the negative impact they are having throughout the diaspora.

In synagogues around the world on Shavuot the Book of Ruth is read, highlighted by its most well-known passage. When instructed by her mother-in-law, Naomi, to return to her own people, Ruth makes one of the most sublime declarations in history:

“Do not urge me to leave you, to turn back and not follow you,” Ruth says. “For wherever you go, I will go; wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Where you die, I will die, and there I will be buried. Thus and more may the Lord do to me if anything but death parts me from you.”

Ruth’s extraordinary act, showing not only love for Naomi but a willingness to accept the One God, makes her part of the Jewish people. And at the end of the story, she gives birth to a son, who in turn becomes the father of Jesse, the father of David, king of Israel. According to tradition, from that progeny the messiah will be born.

The message our rabbis offer up us is a profoundly bold one of acceptance. After all, Ruth is from a tribe that is an enemy of the Jewish people on a deeper level than even the descendants of Esau, the Edomites, or the Egyptians, who cruelly enslaved us for centuries. In Deuteronomy, God says, “You shall not abhor an Edomite, for he is your kinsman. You shall not abhor an Egyptian, for you were a stranger in his land.” But the descendants of Moab, until the 10th generation, should not be accepted into “the congregation of the Lord because they did not meet you with food and water on your journey after you left Egypt” and because they hired Balaam “to curse you.”

And yet Ruth’s straightforward declaration to Naomi not only brings her acceptance among the Jewish people, but also makes possible her pivotal role in determining the kings of Israel and, ultimately, the messiah.

The rabbis of old no doubt struggled with the text of the Book of Ruth — how could a member of a cursed tribe be the heroine of the story and the grandmother of King David? A legal loophole of sorts is found, interpreting the prohibition of marrying a Moabite as applying to Jewish women, thus allowing a man to marry a woman from Moab.

In contrast to this message, I can’t help but think that if Ruth lived under the current Chief Rabbinate of Israel, with its increasingly rigid and restrictive interpretation of the laws of conversion, she would not be accepted as a daughter of Israel, and the trajectory of Jewish history would be altogether different.

Of course it is a great responsibility to define who is and who isn’t Jewish, especially in our modern age of pluralism. The laws are complex, and the stakes are high. But what is most troubling about the views coming out of Jerusalem in recent years is that they are motivated by an effort to keep the gates closed, to prevent sincere seekers from joining our people rather than to welcome them.

Potential converts are told that they must accept each and all of the hundreds of mitzvot of Jewish life when a more welcoming approach would enable tens of thousands of Russians in Israel, who identify with the state and serve in the IDF, to join the Jewish people. The potential for transforming society in positive ways is enormous. Hundreds of Orthodox rabbis in Israel belong to Tzohar, a rabbinic group created in the wake of the Rabin assassination to counter the sense of alienation toward Judaism among many Israelis, fostered by the rigidity of the Chief Rabbinate. The group’s mission is to promote “an ethical, inclusive and united Jewish Israel society.”

At a time when we most need the spirit of Hillel, who warmly received the man who wanted to learn about Judaism while standing on one foot, we have the reaction of Shammai, who shooed him away.

On Shavuot, we mark the day that, according to tradition, all Jews — past, present and future generations — gathered at Sinai and accepted the Torah. It was the greatest moment of Jewish unity in history. In that spirit, reading the story of Ruth on the festival should stir our impulse to embrace rather than reject those who are sincere in their intentions to echo Ruth’s words: “Your God shall be my God.”

Chag sameach.

Note: A earlier version of this column appeared in The Jewish Week in 2012.

בכול הכבוד

Unfortunately, the conversion issues continue to worsen.