The Man Behind The Iconic Image

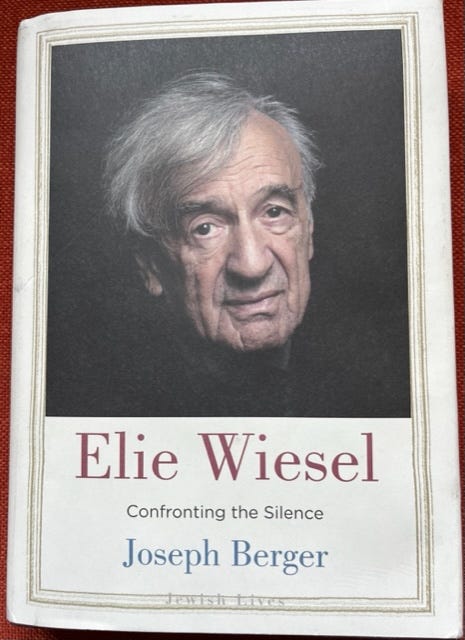

Joseph Berger’s new biography of Elie Wiesel offers an intimate portrait of the Nobel Peace Laureate and modern-day prophet.

It’s hard to imagine anyone, especially a 16-year-old orphan, emerging from the horror of Auschwitz and Buchenwald to become the voice of a generation, effectively calling on the world to take the lessons of the Holocaust to heart.

How did Elie Wiesel, a scholarly yeshiva student from a remote Eastern European shtetl, acquire the gift of language, dignity and courage to become, in the words of the Nobel Peace citation he received in 1986, “a messenger to mankind,” insisting that “the forces fighting evil in the world can be victorious”?

That was the key question Joseph Berger sought to answer in his new biography of perhaps the most famous survivor of the Holocaust, who died July 2, 2016 at the age of 87.

The veteran New York Times reporter spent close to four years researching Wiesel’s many writings – including memoirs, novels, essays and lectures – and interviewing family members, friends, scholars and critics.

As the son of Holocaust survivors who has written warmly about Jewish customs and religious leaders for The Times over the years, Berger was well-suited for – and well aware of – the challenge of writing a biography seeking to capture the profound impact Wiesel had as the conscience of civilized society – including publicly dressing down a President of the United States in the White House – while not ignoring the flaws and foibles that made him human.

The result is “Elie Wiesel: Confronting The Silence” (Yale University Press’s Jewish Lives Series), an elegant, sensitively written portrait that deepens our understanding of and appreciation for one of the most important figures of our time.

At 300 pages (plus 24 pages of notes and meticulous attributions), it is a must-read for anyone seeking a fuller sense of the man himself, in addition to the details of his exceptional career.

“This book was not intended as hagiography,” Berger told me during a recent interview. “I’m a journalist and I needed to make things accounted for,” he said, citing as an example his reporting in the book of Wiesel’s struggles in the early 1980s as chair of the federal commission that led to the construction of the U.S. Holocaust Museum in Washington. Dealing with the politics and finances of the operation was not Wiesel’s strength, as he readily admitted in his memoirs, and after more than seven years with no construction taking place, he stepped down from the post, leaving it to businessmen and developers to see the project through.

The museum opened in 1993, and has been a remarkable success in terms of its design, content and as one of Washington, D.C.’s most visited sites. “More than anyone else,” Berger writes, “Wiesel wrote the books and articulated the sentiments that propelled the Holocaust so prominently onto the nation’s agenda and persuaded American presidents to realize that this shameful history had to be permanently memorialized on the National Mall.”

A Voice Of Memory

The book begins with a description of Wiesel’s idyllic childhood as a quiet yeshiva student in Sighet, a shtetl in the Carpathian Mountains. Berger writes movingly about his subject’s horrific ordeal in the concentration camps, losing his faith in God and his struggle to keep his frail father alive.

From there, Berger leans heavily on Wiesel’s own memoirs in reporting on the young man’s struggles as an orphan in France; scraping by as a journalist for an Israeli newspaper; and the years of loneliness and depression in Paris and New York.

Wiesel’s fortune began to change in 1956 with the publication of the French version of “Night,” a book he had been writing (first in Yiddish, later in French), editing and radically trimming, for years. It was his spare but haunting account of the physical horror and spiritual crisis he endured during two years in concentration camps that launched his reputation around the world as a voice of memory and conscience. The memoir has become part of the curriculum of countless schools around the world and has sold more than 14 million copies to date.

Berger devotes chapters to major moments in Wiesel’s life, like his trip to the Soviet Union in the 1960s that motivated him to write a moving account of the plight of the three million Jews unable to leave or openly practice their religion. Few remember that “The Jews Of Silence” marked the beginning of the movement that over the next 25 years led to the emigration of almost a million Jews to the West, primarily Israel and the U.S.

A chapter entitled “The Bitburg Fiasco” is particularly enlightening as it chronicles in detail how it came to be that in April 1985, Wiesel bluntly criticized President Ronald Reagan in a public ceremony in the White House. This was soon after it was learned that the president, on an upcoming visit to Germany, planned to lay a wreath at a military cemetery for the Wehrmacht, the Nazi army.

In a classic example of truth to power, with Reagan at his side, Wiesel said, “That place is not your place, Mr. President. Your place is with the victims of the SS.”

It was a stunning moment, and as Berger writes, “Wiesel’s remarks … amplified the public attention given to the Holocaust and helped elevate remembrance to a national obligation.”

The reader comes to recognize the wide range and deep impact Wiesel had not only as a prolific writer but as a professor for many years at Boston University, Nobel Peace laureate, global human rights activist, consistent advocate for Israel, and frequent lecturer. (His series of talks at the 92nd Street Y in New York on Biblical figures was the hottest ticket in town for decades.)

Running through it all is Wiesel’s relationship with a God that he at times decried but never denied.

“I’m angry at God, but sometimes that brings me closer to him,” he once told Berger, who as a Times reporter interviewed him a number of times and noted that “he spoke frankly with me.”

Berger said he first met Wiesel on a flight to Israel in 1973, two weeks after the Yom Kippur War began. A charming passage in the book describes the scene on the plane of Wiesel and his close fellow survivor friend Sigmund Strochlitz sitting a few rows in front of Berger, “with their shoes off, humming chasidic melodies to each other.

“Despite their worries about the perils they would encounter in an Israel under siege,” Berger writes, “they radiated the joy of two men heading home after a long absence.”

‘A Complex Figure’

Berger characterized his book to me as “an overwhelming tribute to Elie for bringing a consciousness of the Holocaust to the world.” But he does not avoid dealing with sensitive subjects. He deals with charges that Wiesel “sometimes over dramatized” in his writing, that he may have fictionalized parts of “Night,” that he was thin-skinned about criticism, at times naive about people who benefitted from associating with him and at times accused of manipulating the media to serve his goals.

Berger quotes Thane Rosenbaum, an author and friend of Wiesel’s, who wrote after his death: “Soft-spoken but with the instincts of a Broadway press agent, he knew how to leverage a story and deliver the perfect sound bite.”

And Berger writes: “There might … have been more than a smidgen of calculation in some of his nobler actions and speeches that served him and his cause. … He was a complex figure.”

In short, Wiesel was human.

An innocent in terms of finances, his foundation and personal savings were wiped out in the Madoff scandal in 2008, but in time, several of his wealthy friends helped him recover. He had declining health in his later years and there were times during public appearances that his remarks seemed cloudy.

Berger writes candidly but sympathetically of Wiesel’s “late-in-life missteps,” including making appearances with Harvey Weinstein and spending significant time with Sheldon Adelson and Shmuley Boteach, whose politics were more to the right and far shriller than Wiesel’s.

Berger said that the only changes he made to the book before it was published came after agreeing to let Wiesel’s son, Elisha, read it. “I included some additional comments,” Berger told me, reflecting Elisha’s belief that his father’s views – particularly in newspaper ads funded by Adelson and Boteach that, Berger wrote, included “overheated language that did not sound like [Wiesel],” accusing Hamas of engaging in “child sacrifice” – were indeed reflective of his father’s feelings.

“Elisha’s interpretation of Elie’s decline was different from mine,” Berger told me.

But Elisha spoke candidly with Berger for the book about the burden of being the only child of such a revered hero. He recalled his rebellious teen years when he sometimes had a Mohawk haircut and colored his hair purple, green, blue or red. He said his father told him, “I love you and would walk down the street with you any time. I am not embarrassed … You are my son.”

Though Wiesel knew nothing about baseball, in 1986 he agreed, reluctantly, at his then-teenage son’s urging to accept the offer from the commissioner of baseball to throw out the first ball at a Mets-Red Sox World Series game, soon after the Nobel Peace Prize announcement.

In the days before the game, young Elisha coached his father to throw a baseball well enough not to embarrass him, Berger noted,

What a delightful scene to imagine.

A Personal Addendum:

With Elie Wiesel, circa 2003

I was blessed to have had a warm relationship with Elie Wiesel, dating back to my earliest days in Jewish journalism when he recommended my work for an award in the field.

He was always encouraging. He spoke at Jewish Week Forums, gratis, met with our Write On For Israel students and graciously wrote the Preface to my collection of Between The Lines columns in 2014.

I think his early support, in part, reflected the fact that he struggled on his own early in his career as a reporter for Hebrew and Yiddish newspapers, so he empathized with someone in his 20s who was serious about the profession.

At one point in the 1980s, when I was editor of the weekly Baltimore Jewish Times, I somehow persuaded Elie to write six columns a year for us. He kindly accepted but insisted that first I find a local, reputable translator of French for his approval, which I did.

Here’s how we worked it out: Elie would fax me his typewritten essay in French, I then faxed it to the translator, she translated it into English and faxed it back to me, I read it over (rarely making edits) and faxed it to Elie, he would review it (and sometimes made edits) and faxed it back to me. And then we published it.

(This would not have worked if we were a daily.)

Soon after Elie won the Nobel Peace Prize, he came to Baltimore for a speaking event, and held a major press conference at a downtown hotel. Arriving late, and entering from the back of the crowded room, I tried to make my way quietly toward the cluster of reporters.

Noticing me, Elie stopped mid-sentence and called out: “Oh hello, Gary, would it be alright if I send my column in a day late?”

I can’t begin to describe the puzzled stares on the faces of all those reporters who had turned around and no doubt were thinking: “Who is this guy?”

For a fleeting moment, I was tempted to reply, “Well, ok, but don’t let it happen again.”

I just smiled.

Dear Gary. It’s Cantor Joseph Malovany. I have just read your review of the book by Joseph Berger on Elie. You write so very well and may I say that it touched me deeply. Each person had had a different relationship with Elie. Elie spoke often to me about those relationships even during his last days of his life. But you truly captured the spirit of the book and of course who Elie was. In the book I am writing now a large section about my close friendship with Elie will be told. It’s going to be a while until the writing of the book will be completed.

I was very please to read you essay. A very big Yishar Koach to you.

Warm regards,

Joseph Malovany.

Wow, thank you for the fantastic piece. It sounds like a great book although it may be hard to read the less than favorable parts of it.

Why is it so hard to accept that even the greats are human, especially after they’re gone? Maybe we think we can learn more from them if we sweep their humanity under the rug and make them into God-like figures. In reality, it is precisely their humanity that makes their greatness so great.