The World War II Hero Who Lived Upstairs

For Memorial Day, remembering the vital role more than a half-million American Jews in uniform – and one I knew well – played in defeating Hitler and his allies.

Dear Reader,

There are nearly 3 million Americans serving in our armed forces today.

I suspect few of us know any of them well. The draft ended more than 50 years ago (July 1973), relieving 18 to 25 year olds of the burden of conscription, but widening the societal gap in this country between those who volunteer to serve and those who choose not to.

Memorial Day in America is marked more with celebration (parades, fireworks, shopping sales and car races) than solemnity, reflection and gratitude to those who protect us today and those who gave their lives for our country, for us.

The holiday here has a very different feel than Memorial Day in Israel, where almost every family has suffered the loss of a loved one or friend defending the world’s only Jewish state.

To mark the annual holiday, on May 27 this year, I offer an essay in honor of all those who have served and are serving now in the U.S. military. Written 20 years ago, this piece seeks to inform or remind us of the tremendous contribution American Jews made in blood and guts in fighting the Nazis and their allies – and describes how I came to appreciate one of the war’s heroes.

Gary

This column, slightly revised, was first published July 30, 2004 in The Jewish Week.

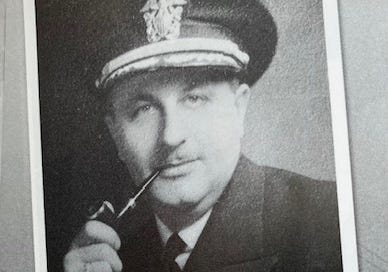

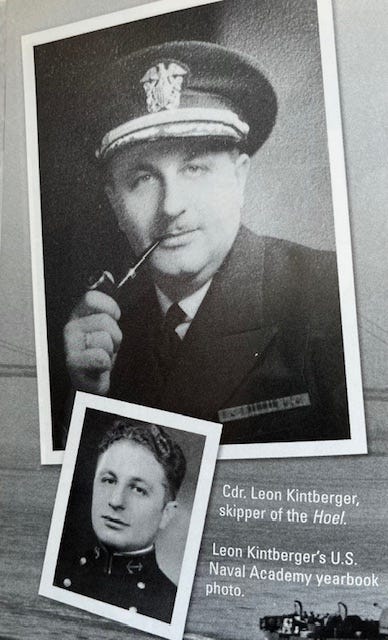

Profiles in courage: Photos of Adm. Kintberger from James D. Hornfischer’s book, “The Last Stand of the Tin Can Soldiers: The Extraordinary World War II Story of the U.S. Navy’s Finest Hour.”

I grew up living downstairs from a genuine World War II naval hero but didn’t realize it until I was well into adulthood. Now, through a series of seemingly fated events in recent weeks, he may be getting the recognition he has long deserved, albeit more than 20 years after his death.

My parents, brother and I lived on the first floor of a two-family apartment in Annapolis, Md. Our upstairs neighbors of 18 years and dear friends of my parents were Leon and Dora Kintberger. Dora, now 95, is still one one of my mother’s closest friends. She and Leon were my godparents.

I best remember Leon as a hearty, dashing figure always holding or puffing on a pipe. He served as president of he local synagogue; my Dad was the rabbi. But Leon had another life I knew little about. A U.S. Naval Academy graduate and career officer, he was the captain of a destroyer that saw heavy combat in the Pacific during World War II, and he retired from the Navy with the rank of rear admiral.

He rarely if ever talked about his harrowing experiences, but I’d heard that his ship had been sunk by the Japanese in a major naval battle. About 10 years after the war’s end, when he was commanding a destroyer, the USS Zellers, Adm. Kintberger gave my father, older brother and me a tour of the vessel when it was in Annapolis. What I remember most, as a boy of 8, was the enormous size of the ship, where men could walk inside its artillery guns.

What brought all this to mind in recent days was a conversation I had with Robert Morgenthau, the New York district attorney, who was encouraging me to visit the exhibit at the Museum of Jewish Heritage’s new wing, named in Morgenthau’s honor, on American Jews who served in World War II.

The exhibit, “Ours To Fight For: American Jews in the Second World War,” has been extended until at least the end of the year. It is a must-see for anyone who wants to appreciate the depth of Jewish involvement in the war effort – 550,000 Jews served – but more of that later.

A World War II vet, Morgenthau told me he served on several ships in the Pacific that had been under heavy enemy attack. I mentioned my close relationship with Adm. Kintberger and said that his ship, the USS Hoel, had been sunk. I later learned that 267 of the 325 crew were killed.

Morgenthau seemed keenly interested, and several days later faxed me a copy of a typewritten Naval archives biography of Adm. Kintberger from Aug. 10, 1957, noting that “he was awarded the Purple Heart and decorated with the Navy Cross, while his unit earned the Presidential Unit Citation” for its “successful engagement with the enemy.”

The Navy Cross is second only to the Medal of Honor in military awards. The citation for Leon Kintberger reads, in part: “For distinguishing himself by extraordinary heroism in action against an enemy of the United States” … for “personal courage and determination in the face of overwhelming enemy surface gunfire and air attack” … and “in keeping with the highest traditions of the Navy of the United States.” Adm. Kintberger also received the Silver Star, which ranks third in the military, among the dozen awards he earned in his career.

According to the report, in the fall of 1944, three months after Kintberger took command, the Hoel and several other destroyers were able to thwart the Imperial Japanese Battle Force’s “attempt to sink our carrier force by what historians have described as “one of the most gallant and heroic acts of the war.”

Excited by the news, I called Adm. Kintberger’s daughter, Suzanne (who used to be my babysitter) to share this information, and to encourage her, at Morgenthau’s suggestion, to send a photo of her father in uniform to be included in the museum’s gallery of Jewish combatants. She, in turn, told me of a new and highly praised book, “The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors,” by James Hornfischer. Only when I read its full and dramatic account of how a small American flotilla took on the mightiest ships of the Japanese Navy on Oct. 25, 1944, off the Philippine island of Samar, did I come to realize the depth of Leon Kintberger’s contribution and bravery.

“Facing overwhelming firepower, with no prospect of reinforcement, 13 American warships began a fight they couldn’t win,” the book notes, “and fought it to the death.”

High seas heroism: the cover of Hornfischer’s book, published in 2004.

The USS Hoel was one of five ships destroyed in the battle, and Leon Kintberger, its captain, is a primary character in the narrative. At one point, writing of the harrowing gunfight at sea, Hornfischer tells how Kintberger steered his ship through enemy fire, “testing his luck, keeping his ship from falling under the arc of the shellfire. His voice was steady and sure.”

Lt. John Dix, the Hoel’s communication officer, kept notes of the battle and described the captain’s commands and demeanor. “‘Right full rudder. Meet her. Steady up. Now full left rudder. Give it all you’ve got.’ He never once let up. He’s calm and firm. Damn but that guy’s magnificent today.”

I felt both thrilled and saddened to read the account, only now realizing how little I knew when I was growing up of Adm. Kintberger’s heroic accomplishments, none of which I ever heard him mention.

My visit to the Museum of Jewish Heritage exhibit took on an added dimension for me of not only learning how many Jews served in and were impacted by the war – 11,000 killed, 40,000 wounded, 52,000 decorated for gallantry – but also allowing me to honor a close family friend and authentic hero.

The award-winning exhibit immediately engages a visitor in wartime experience through films, photos, letters, artifacts and, most moving, personal audio and video testimony, including such notable veterans as Ed Koch and Robert Morgenthau. One learns that some Jews experienced intense anti-Semitism in the service, others none at all. But the fact that their brethren in Europe were being slaughtered by the millions heightened the sense of purpose for their combatants, whose exploits on land, sea and in the air are detailed.

Near the end of the exhibit, a long wall contains a rotating, and frequently updated section that features some 200 photos of those who served. I looked at the faces carefully, some grim, some smiling, and I thought of those I know whose fathers saw combat. And I recalled Leon Kintberger, who returned to civilian life, helped lead and oversee the construction of a shul in Annapolis only 15 years after the destruction of his ship in the Pacific, with the loss of so many men. The arc of his life was a reminder to me of the 20th century American Jewish experience of commitment, sacrifice, faith and renewal.

I only wish I could thank him today.

Postscript: The exhibit was on display in New York for more than two years, through December 2005. It has been presented at other museums since then, including Holocaust museums in Houston and Chicago.

Both my parents served in the US Army in WWII, as did 2 of my 3 uncles -- the 3rd worked as a civilian in a defense plant. I actually don't know if my father volunteered or was conscripted. My mother volunteered because she wanted to 'fight' the Nazis, and requested a transfer overseas, when she felt she wasn't 'doing enough for the war effiort' on a base in the midwest.

Thanks for sharing this. Some things are worth repeating.