Where Israel’s Past Meets Its Future

The People of the Book have a magnificent new home base. It not only houses historic and cultural treasures but projects a brighter tomorrow.

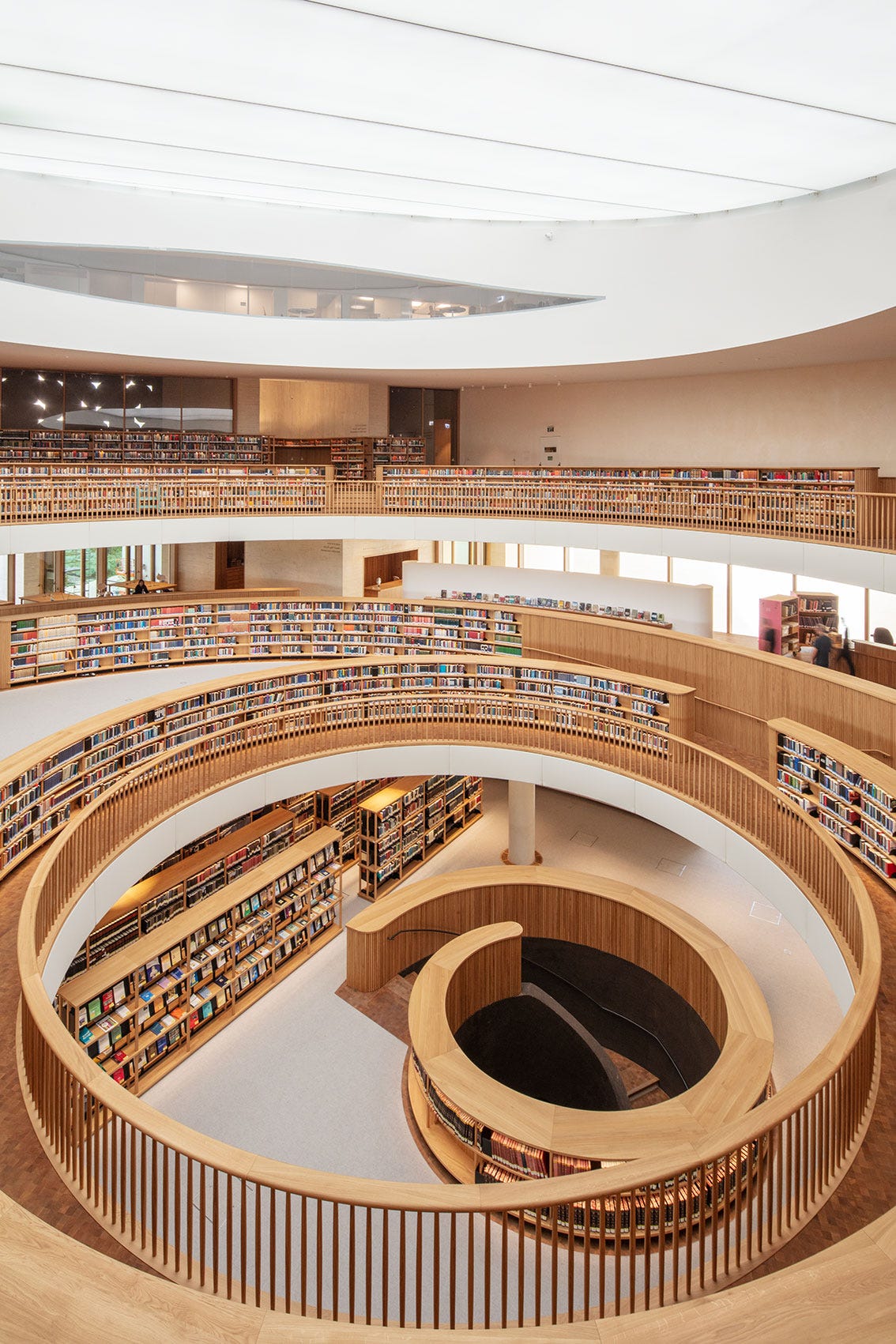

The Well of Knowledge. That’s how the National Library of Israel describes the bottom of its three-story reading rooms.

In August 2020, a headline in Haaretz read: “Israel’s National Library Is Closing Down. How Much Do You Care?”

Not much, it seemed.

The library, located on the campus of Hebrew University for more than 60 years, was a bit out of the way for many, and its major historical and cultural collections of Israeli and Jewish life were not easily accessible. Suffering from budget cuts, dwindling donations and maintenance problems, the institution was forced to put its 300 employees on unpaid leave and halt most of its services for several weeks.

Fortunately, though, an ambitious plan to build a new home for the library, officially named the National Library of Israel in 2008, had been launched in 2014. Major funding for the more than $200 million project came from the Rothschild family through its Yad HaNadivFoundation, the Gottesman family of New York and the government of Israel. Construction began in 2016 in a prime Jerusalem spot, between the Knesset and the Israel Museum, and after numerous delays, the majestic structure was ready for its much-anticipated grand opening the week of October 17.

The horrific Hamas attack on October 7 forced an abrupt cancellation of the various celebratory events. But like so many other elements of Israeli society, the leadership and staff of the library pivoted quickly and were able to open its doors to the public for the first time on October 29.

Weekly tours of the 11-story building – five below ground – are the hottest ticket in town, and my wife and I were fortunate to be part of a small private tour led by Naomi Schacter, director of international relations and partnerships, late last month.

On entering, the initial impression is breathtaking — seeing the size and beauty of the curved-roof building, and realizing that the new home of the People of the Book is an architectural wonder deserving of its lofty mandate “to collect, preserve, cultivate and endow treasures of knowledge, heritage and culture, with an emphasis on the Land of Israel, the State of Israel and the Jewish people in particular.”

Schacter reflected the excitement of the staff, board of directors and an Israeli society that at last, 131 years after its founding, has a worthy home for the largest Jewish collections in the world of books (4.5 million), photographs (2.5 million), archives (1.4 million), manuscripts (600,000), articles (600,000), and recordings (120,000), as well as thousands of maps, posters, videos and newspapers.

More impressive than the numbers, though, is the institution’s dynamic role in preserving and furthering the Jewish people’s collective memory, telling the story not only of a people that goes back many centuries but of a nation in the midst of the most horrific war in its history.

The first major decision by the library after its opening was to launch a major project, “unprecedented in its scope,” Schacter said, to thoroughly document October 7 and its aftermath. Entitled “Bearing Witness,” and supported by the Ministry of Heritage and a growing list of partners around the world, it is engaging virtually every department of the library in collecting oral and written testimony, documentation, audio and visual material, and social media coverage. The goal is to create “a national memory database,” ensuring that the facts of the Hamas attack will be available to future generations and to today’s truth-deniers.

The project will also track the impact of October 7 on Jewish communities around the world, including the spike in anti-Semitism and security concerns among citizens and students on campuses. “We ensure that no story goes untold,” according to a library statement.

Wall of victims. Naomi Schacter, our guide, opened her tour remarks with the faces of the victims of October 7 projected on the wall behind her.

A Peaceful Presence in a Time of War

The overarching mood of sadness in the midst of the ongoing war was evident from the outset of our tour when Schacter spoke to us in front of a huge wall with the faces of hundreds of Israeli victims of the October 7 attack projected on it. And later, she showed us a poignant exhibit, entitled “Every Hostage Has a Story,” that features a poster of each hostage on the back of a chair, with a book on each seat – that person’s favorite book, chosen by a family member, waiting for them on their return.

‘Every Hostage Has a Story’: An exibit of chairs with the photos and favorite books of those who were kidnapped October 7.

The tour itself offered glimpses of the full range of treasures from the Jewish and Muslim worlds, including incantation bowls dating back to the 5th century; a first edition of the Babylonian Talmud; commentaries on the Mishnah by Sephardic Torah scholar Maimonides (1138-1204) with corrections in his own hand; a more than 900-year-old Koran; and an 11th century copy of the Book of Healing by the Muslim philosopher Abu Ali Ibn Sina (also known as Avicenna).

Contemporary items on display include the first draft of Naomi Shemer’s iconic song, “Jerusalem of Gold”; the writings of David Grossman and A.B. Yehoshua; a note found on Hannah Senesh, the young poet and fighter, the day she was executed by a Nazi firing squad; and a correspondence between Ilan Ramon, Israel’s first astronaut, and Yeshaya Leibowitz, an Orthodox Israeli public intellectual.

As we walked through the building, we viewed the below-ground, climate-controlled area where a robotic retrieval system stores 50,000 books and can pick any one of them up so that it can be brought to a reader in a few minutes. We learned how the library is dramatically increasing its digital collections and making them available online to people around the world. Spending time in the Main Reading Hall in the center of the building, with three circular floors of books and a huge circular skylight at the top, one feels both the grandeur of the space and the warmth of humanity in the room. As Oren Weinberg, CEO of the library has noted, the goal was “not simply to house books but to have them used by people.”

Indeed, most impressive during our visit was how filled the rooms were with readers. Clearly, the library has become a welcome, peaceful and calming environment in a time of war. Schacter, our guide, emphasized that the library and its resources are free to all, and that attendance has been unexpectedly high, drawing people from all walks of life, Jewish and Arab.

Rachel Neiman, who is in charge of international public relations at the library, described the public response as “overwhelming.” For the casual visitor, she said, “people first walk in and say ‘wow,’ and then they feel a sense of pride and order at this crazy time. For our core audience of researchers, this is becoming a second home. We want everyone to come.”

In addition to in-person visits, people around the world can benefit from Zoom events and can access countless materials online.

New kid on the block: The National Library of Israel was built between The Knesset and The Israel Museum.

“The library doesn’t want to be just a repository of antiquity,” Jonathan Sarna, a professor of American Jewish history at Brandeis University who has had a long association with the library, told me. He said he is impressed that “this is everybody’s library,” unlike many university libraries in America that are exclusive to students and faculty. He said the library is “taking very seriously its role in representing the whole state and is trying to acquire important Arab materials.” He also stressed the vital role the library can play in helping Israeli and American Jews, who together make up 90 percent of world Jewry, in learning more about each other. “It’s crucial,” Sarna said, “and this war has made it even more important that we be in closer touch.”

Jay Pomrenze, a retired bank executive in America who made aliyah with his family three decades ago, played a key role in strengthening the library’s ties to the diaspora in serving as the first chair of its American board. He helped bring on distinguished members, including Ambassador Dan Kurtzer and historian Paula Fredriksen, to build support for the library.

Pomrenze, a close friend, said he agreed to accept the voluntary post in part to honor his late father, Col. Seymour Pomrenze, a National Archives archivist who was one of the famed Monuments Men who helped sort through and return valuable books and art looted by the Nazis after World War II.

“It was a natural connection for me,” he noted, in appreciating the importance of preserving historic and cultural treasures.

In addition, he said he valued the library as an all-too-rare “unifier” in a politically and religiously divided society of Jews and Arabs.

Newspapers As ‘A Window Into Jewish Life’

On the tour of the library, we visited a room featuring the newspaper collection of millions of pages from hundreds of newspapers – Israeli, Jewish, Arab – in many languages, dating back to the late 18th century. A young man was looking through a bound copy of The Forward, then a Yiddish daily, from 1927, as his toddler played nearby.

I was especially interested in learning more about the Historical Jewish Press project, an online archive of nearly 800 Jewish newspapers from many countries in more than a dozen languages, sponsored by the library and Tel Aviv University. Most of its five million pages are available digitally to interested readers around the world.

Eyal Miller, manager of the project, said that much of the material is from the 19th century to the present day, and the overall goal is to collect, preserve and make accessible the content of every Jewish newspaper in the world. But funding and copyright concerns are an issue, and only a handful of current American Jewish publications are on the site now. (Miller and several other library officials I met told me they are most eager to have access to The New York Jewish Week archives, dating back to the late 1960s, and are hopeful that will happen soon.)

“We want to fill the gap,” Miller told me.

He described his work as “a lot like being a detective,” seeking to locate Jewish newspapers or missing issues from countries around the world. “A Jewish community, until recently, consisted of a synagogue, a cemetery, a kosher butcher and a Jewish newspaper,” Miller said, noting that newspapers are becoming more rare.

He said what he loves most about his work is “traveling the world every day” from his computer, and having “a window into Jewish life,” past and present, by reading “the mundane – who got married, who owes money, the local ads, the restaurant menus.

“Almost any information you want to know about Jewish life starts with the Jewish newspaper,” he said.

He might have added that almost any information you want to know about Jewish life can be found in the National Library of Israel. On leaving the building, I felt a sense of gratitude that it has already become a cultural oasis during these dark days, a reminder that the institution is committed to telling our unique story – past, present and future.

Physically stunning with awe-inspiring content.

Thanks Gary.

Ahhh, newspapers...

On a serious note, I do feel that a visit to the new library (which must include a tour), the ANU Museum (the former Beit Hatesufot) and Yad VaShem will be a crash course for any visitor to Israel -- Jewish or otherwise -- to the many iterations of what Jews are today and how that came to be.