‘Read All About It!’ Two Centuries Of Jewish News At Your Fingertips!

How the technology of the future is preserving the news of the past at the National Library of Israel.

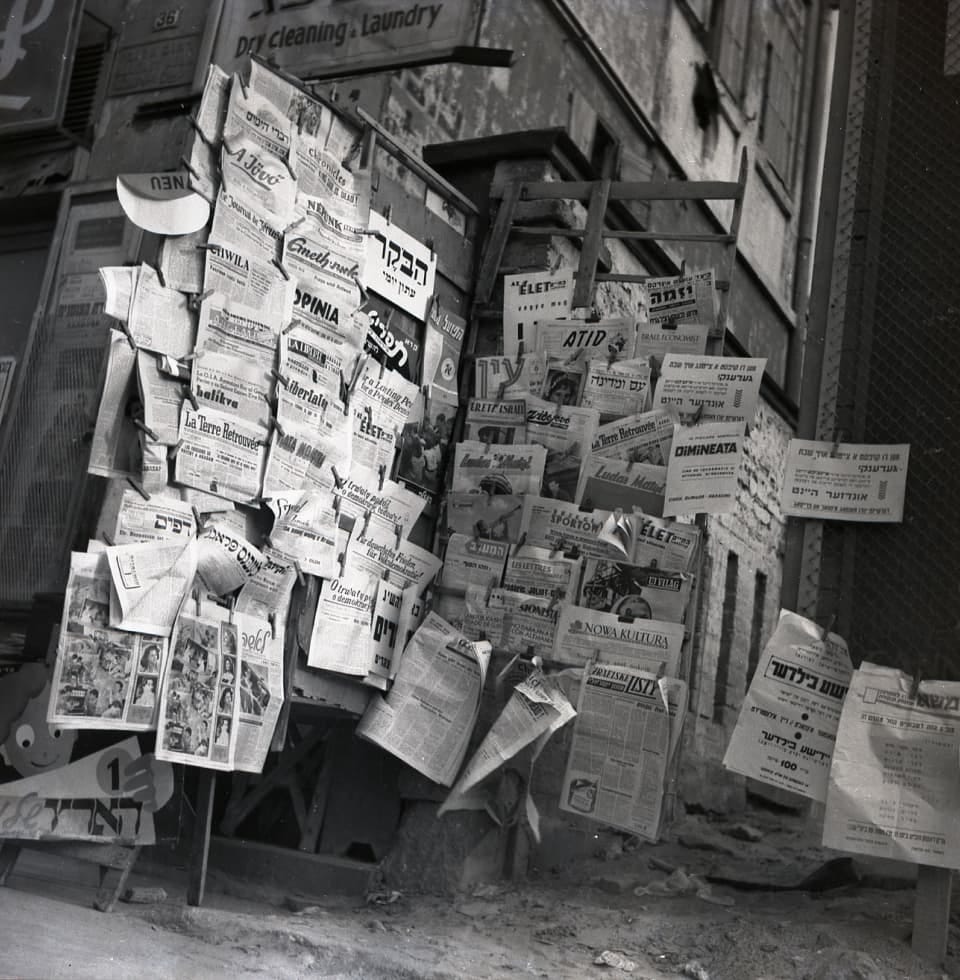

Jews love their news: A classic newsstand photographed by Beno Rothenberg. (National Library of Israel.)

Dear Reader,

During these deeply worrisome times, when Israel’s ongoing war has made the country an international pariah, when anti-Semitism in America and around the world has continued to surge, and growing numbers of Jews in Israel and America fear for their country’s respective democracies, much attention is being paid to the role of journalism and its impact on society.

Is mainstream media’s high-profile impatience and anger with Israel a reflection of its audience — or is it leading the way? Is the Trump administration’s intense pressure on elite universities to strengthen their policies to protect Jewish students actually helping the students or causing more negative sentiment toward them?

What is clear is that who and how a story is told is of paramount importance — not only in the moment but in how it will be interpreted and studied years from now. This report on an ambitious international project to reach and impact Jewish communities around the world seems especially timely. As its host, the National Library of Israel, notes, “providing access to primary source material, particularly in an era where truth is elusive, is increasingly important.”

Gary

Back in the mid-1970s, when I became editor of the Baltimore Jewish Times, I sometimes would spend a few minutes alone during a lunch break in the office of the publisher, my mentor and friend, the late Charles “Chuck” Buerger. I loved looking through the big, black bound volumes of the weekly paper – going back to its founding in 1919 – that filled his bookshelves. There were times I searched for a specific article or was curious to see the local angle of how the paper covered major international events, like Kristallnacht in Germany in November 1938 or the founding of the state of Israel in May 1948.

Other times my interest was more personal. Scanning the community social pages from back volumes, I found my bar mitzvah announcement, including a photo of me smiling through my first set of braces. Going back to 1938, I found my parents’ wedding announcement with a photo of the handsome couple and a list of prominent rabbis in attendance.

Even during those long-ago searches I was aware of how precious those volumes were, not only because they held the lived history of the Baltimore Jewish community – the major news stories and the everyday activities – but because their pages were so fragile. Yellowing and brittle, the edges sometimes came off in my hands. Five decades later I wonder what kind of shape they are in now.

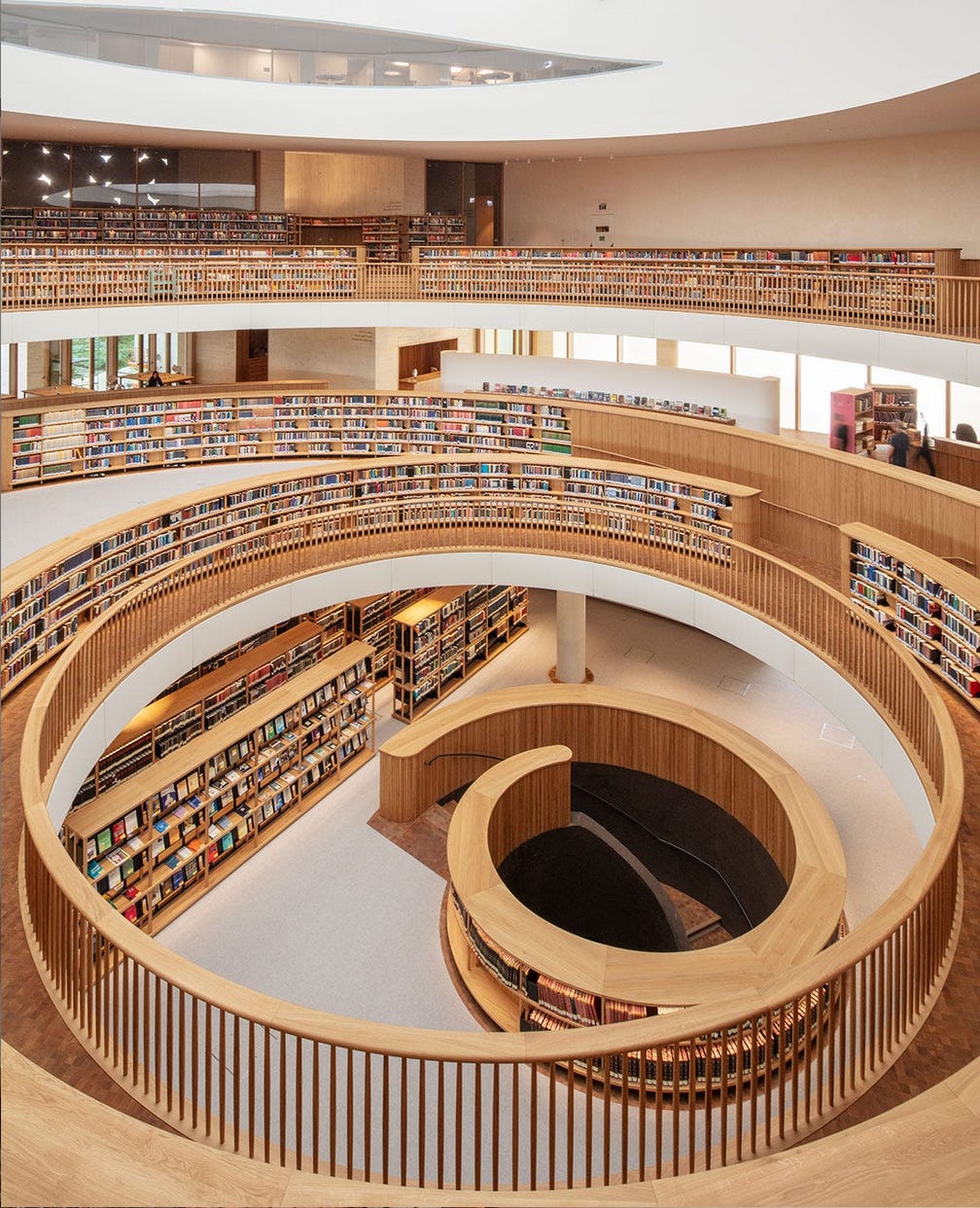

Fortunately, the National Library of Israel (NLI) is ensuring that Jewish newspapers from around the world are part of its mission to collect and preserve treasures of Jewish history and culture. Since 2005, the library, now housed in a magnificent 11-story building – five below ground – in Jerusalem, has overseen the Historical Jewish Press project (Jpress), a unique online archive. It consists of more than 500 Jewish newspapers from many countries in more than two dozen languages, sponsored by the library and Tel Aviv University. Most of its more than five million pages, dating from the 19th century to today, are available digitally and free to readers around the world.

The Well of Knowledge. That’s how the National Library of Israel describes the bottom of its three-story reading rooms.

This past spring, NLI marked the 20th anniversary of the project with a three-day conference at the library to highlight the impact of Jpress. More than 100 researchers, writers, journalists and educators took part in sessions that dealt with the past, present and future of Jewish newspapers. They included what makes the Jewish press ‘Jewish’; women (including Orthodox women) writing in the Jewish press; reports on 19th century Jewish newspapers in Europe, Iraq and South America; and how creative writers use the Jewish press in their research and work.

The topics may sound geared toward academics, but Eyal Miller, manager of the Jpress project, emphasized in a Zoom interview that the program – and the initiative – was not only for scholars but for anyone and everyone interested in learning more about the political, cultural and social influence of Jewish communities in more than two dozen countries over the last 240 years.

“The tool is super useful for anyone,” he said. “It’s a gold mine. Almost any information you want to know about Jewish life starts with the Jewish newspaper.” Miller pointed out that “newspapers were meant for the masses, and digitization is the democratization of knowledge.” He said he loves “the detective part” of his work, seeking to locate Jewish newspapers or missing issues from countries around the world. “Every tiny Jewish community had a synagogue, a kosher butcher, a cemetery and a newspaper,” though he acknowledged that newspapers are becoming more rare.

Renowned Brandeis University scholar Jonathan Sarna, who has been instrumental in his support of the NLI and its Jpress project, noted that while the Holocaust decimated Eastern European Jewry and its many Yiddish newspapers, “much of that world can now be brought back and studied. And NLI’s reach is everywhere.” He also pointed out the importance of Jewish newspapers from major Arab cities like Tangiers, Cairo and Beirut that reported on how Jews were driven out of Arab countries during the 20th century, especially after Israel became a state in 1948.

Sarna offered an example of how he has used Jpress in researching the life of Sholem Aleichem, the famed 19th century Yiddish author and playwright, for a new biography he is writing. Sarna told me he wanted to find out if a storied meeting between Mark Twain and Sholem Aleichem in New York in 1905 really happened. According to the legend, on being introduced to each other in New York, Twain was told, “you’re meeting the Jewish Mark Twain,” to which he replied, “tell him I’m the American Sholem Aleichem.”

Nice story, but was it true? Using Jpress, Sarna found reports in the American Jewish press and Yiddish press at the time that Twain did attend Sholem Aleichem’s play “The Prince and the Pauper” and that the two men were introduced. Whether or not the quoted exchange actually took place remains unknown. “It sounds too good to be true,” Sarna said, “but it’s plausible that they did meet. And I never could have found that out” without Jpress, Sarna said, adding that “a new generation of historians with technical prowess that I don’t have will be able to do all sorts of new studies.”

A highlight of the conference was the announcement of the most recent major acquisition for Jpress: The Jewish Week of New York, described by Sarna as “the most important American Jewish newspaper of its time,” covering the highest populated Jewish city in the world. Thanks to a very generous donation by Eric Goldstein, CEO of UJA-Federation of New York, and his wife, Tamar, nearly half a century of the paper’s issues – May 1971 through June 2018 – are in the process of being digitized, and soon will be available on the Jpress website. In all, that adds up to more than 2,400 issues, about 100,000 pages. (I was grateful to have been at the helm of the paper for about the last 60,000 of those pages.)

Michelle Margolis, the Norman Alexander librarian for Jewish Studies at Columbia University, took part as a panelist at the conference. Her connection with Jpress is through a collaborative group made up of Jewish studies librarians at Columbia, New York University and the New York Public Library that provide research to NLI almost exclusively through digitization. She told me that Jpress “clearly changed the landscape not only for scholars but even casual learners and high school students.” Genealogical buffs, take notice.

Observing that “Jewish media of the time, in the 19th and 20th centuries, was social media,” Margolis said American Jewish newspapers were filled with stories of human experiences otherwise forgotten. For example, she said Yiddish newspapers listed “a gallery of missing husbands” who left Europe for America.

On a personal level, she said she found the name of her grandfather among other names in a 1939 newspaper ad of Jews in Europe desperately seeking passage to Palestine. He later became a rabbi in Boston.

“So many treasures can be found” through Jpress and the numbers will only grow as the project becomes better known, Margolis said.

The final session of the three-day conference featured several leading Israeli journalists discussing the state of the press in Israel, and the tone was less than optimistic, according to Jpress manager Eyal Miller. “They spoke of the need for journalists to adapt to reality,” including the enormous impact of social media and the furious pace of constant news to absorb. “They said the role of journalists today is to make sense out of it all,” Miller told me.

That has been — and always will be — the job of the press, but it has never been as complex and challenging as today. Newspapers and all print media are going the way of the horse and buggy in the age of the internet, podcasts, Facebook, TikTok and Instagram. Social media reigns, but it is a decidedly mixed blessing. It pumps out huge volumes of information every day but much of it is false, easily manipulated and circulating freely without standards. And reflecting our binary society, the media, too, increasingly is divided among political lines rather than striving for objectivity.

In the U.S., Jewish “weaklies,” as Rabbi Stephen Wise used to call them — with good reason — a century ago, still tend to lack a strong, independent voice. Often published by, or in some ways beholden to, local federations or other prominent Jewish organizations and lay leaders, they tend to have small staffs and budgets, rely on outside news services for national and Mideast coverage, and too often avoid communal controversy. The editors often walk a tightrope between journalistic integrity, which includes uncovering problems, and a sense of civic Jewish responsibility, which usually translates into covering up delicate issues in the name of protecting the community.

In truth, though, the community loses when its problems remain in the shadows. Because they don’t go away. And it’s the reporting that goes deeper that will be remembered in future archives that will tell the story of this generation and those to come. But that depends on whether there are committed and credible journalists and media organizations to continue the centuries-long tradition of recording our history. I truly hope so, and if that’s the case, creative initiatives like Jpress will be at the forefront of collecting, preserving and analyzing that eternal story.

Well said, Neil, as always. Maybe future historians will remember our quintessential Jewish telegram (whatever THAT is..): "Start worrrying; details to follow."

This is an important project. Sadly, it comes too late for scores of community newspapers forced to stop publishing as organizations, facing budget challenges, changed priorities. Besides losing the contemporary history of the community, they sacrificed the tool that knit the community together. To add insult to injury, the historical record became landfill.